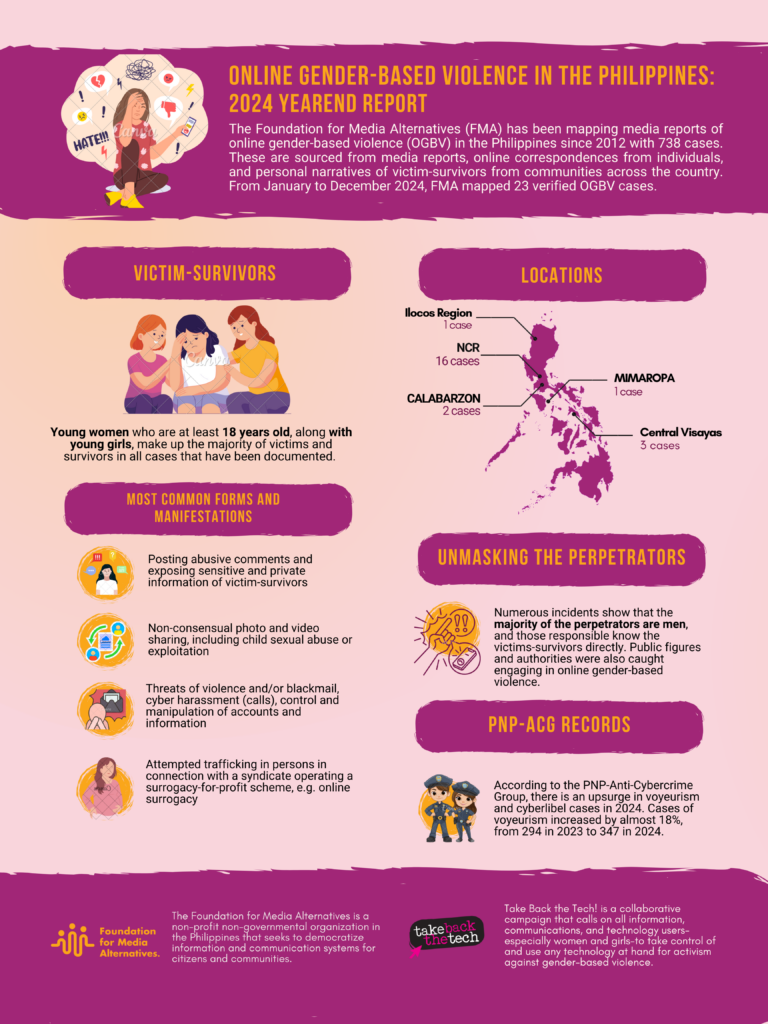

2024 Online Gender-Based Violence Report

Information and communication technologies (ICTs) and the Internet have transformed the lives of many Filipinos across the world. The advancement of these technologies revolutionized the way we socialize and transact business, but most especially, how we gather and receive information.

For women and gender-diverse groups, ICTs and the Internet have given them significant spaces to assert their rights and identities. It is also in these spaces that they can initiate and strengthen their engagement in political and public life. However, as ICTs proliferate and become more widely used, there is concern and evidence that gender-based violence, including the use of technology, is on the rise.

What is online gender-based violence?

While there is no universally accepted word for online gender-based violence (OGBV), it is any act that is mediated by the use of information communication technologies or other digital tools such as internet intermediaries, which results in physical, sexual, psychological, and social harm.

It occurs in a variety of contexts and through various media, including misogynistic remarks, sexual harassment, doxxing, and the non-consensual dissemination of intimate images to cyber-stalking, among others. Over the years, this type of gender-based violence has escalated, posing significant threats to the safety and well-being of women and other vulnerable groups due to its unique characteristics, including its global nature, the fluidity of digital personhood, the lack of materiality, anonymity, and intractability.

How prevalent is technology-facilitated gender-based violence?

Despite the breakthroughs in institutionalizing the protection of women around the world, gender-based violence continues to persist and affect many women and minority groups.

According to the United Nations Population Fund, nearly 60% of women globally have suffered online violence, whether on their phones or online. They are subjected to toxic social media messages, hate speech, and violent content, or their photographs are sexualized, distorted, and published without their consent. The prevalence of online gender-based violence varies significantly by area, according to The Economist Intelligence Unit’s 2020 report; 85% of women who spend time online have seen internet violence. 38% of women have been the victims of online abuse. One global study found that 58% of girls and young women have experienced some form of online harassment.

Based on the recent data of the Philippine National Police, there was a 13.51% drop in index crimes in the first 10 months of 2024. Out of 30, 322 index crimes, 3,494 cybercrime cases from July to September this year compared to 3,707 in the second quarter, and 4,354 in the first quarter. Online scam cases topped the list of cybercrimes logged in 2023 at 14,030, followed by identity theft at 2,804 and cyber libel at 1,182 Other cybercrimes logged in the past year include online threats (552); data interference (412), computer-related fraud (171), love scams (168), sextortion (121), and online violence against women and children (32).

In a separate public announcement of PNP-ACG in January 2025, there is an upsurge in voyeurism and cyberlibel cases in 2024. Cases of voyeurism increased by almost 18%, from 294 in 2023 to 347 in 2024.

OGBV case-mapping

Since 2012, the Foundation for Media Alternatives (FMA) has mapped 738 cases of OGBV in the Philippines through media reports. Over time, these cases have shown tendencies and emergent expressions of GBV that are reproduced and aggravated through ICTs.

Between January and December 2024, FMA documented and verified 23 new cases of online gender-based violence. Young women who are at least eighteen years old, along with young girls, make up the majority of victims and survivors in the documented cases. These individuals are primarily from the National Capital Region, two from the Calabarzon region, three from Central Visayas, specifically Cebu province, one from Mimaropa, and one from the Ilocos region.

The most common manifestations of documented OGBV in 2024 are abusive comments that harass and/or expose sensitive and private information of victim-survivors; sharing of non-consensual photos and videos; threats of violence and/or blackmail; control and manipulation of accounts and information; and identity theft or falsification.

It is crucial to highlight that these statistics do not provide a whole picture of OGBV instances in the Philippines, as many stories go unreported or undocumented. It is also important to keep in mind that a victim or survivor may suffer from various forms of abuse or harm and that a single case may fall under multiple violation categories.

Unmasking the perpetrators

Numerous incidents show that the majority of the perpetrators are men, and those responsible know the victims-survivorsdirectly. There were also concerning instances where public figures and authorities were caught engaging in online gender-based violence. For instance, an ex-Cebu City councilor is facing a complaint before the prosecutor’s office in Pasay City for allegedly taking pictures under a female lawyer’s skirt before a Cebu-bound flight at the Ninoy Aquino International Airport (NAIA) in February. Maria (not her real name) filed cases against the public figure on March 19, 2024, for alleged violation of Section 4(a) of Republic Act (RA) 9995, or the Anti-Photo and Video Voyeurism Act of 2009, and Section 4 of RA 11313, or the Safe Spaces Act. This was the second filing of the cases. She originally filed allegations against the culprit with the Lapu-Lapu City Prosecutor’s Office, which dismissed them because it lacked jurisdiction.

In several circumstances, police officials were either under investigation or relieved from their posts after their subordinates filed complaints for alleged sexual harassment.

Another case is a teacher in Misamis Oriental who has been detained for allegedly assaulting his minor students and selling their images and videos online. Police secured a search order and rescued six young people—four boys and two girls—from the 43-year-old suspect’s residence. They also discovered sensitive photographs and videos of the victims, as well as the equipment used to film them. According to the investigation, the suspect would invite his students and past students to his home, where he would molest and record graphic images and films of the victims.

Online violence can extend into physical spaces, just as physical violence can extend online. This inescapable online-to-offline cycle of abuse exacerbates the suffering the victim-survivors face after experiencing this form of abuse.

Online Surrogacy: A New Scheme of Human Trafficking

Twenty Filipino women were rescued from human trafficking occurrences in Cambodia in the final quarter of 2024. These women were trafficked as surrogate mothers.

Of the twenty women, seven (7) were returned home, and the other thirteen (13) in various stages of pregnancy are currently under hospital arrest in Cambodia and sentenced to two years in prison for breaking Cambodia’s surrogacy and anti-trafficking laws. The women were sent to Cambodia, where surrogacy is illegal, after being recruited online to travel to Cambodia.

The Bureau of Immigration said in a public statement that the Commission is concerned about the growing number of incidents of women being trafficked overseas for illegal surrogacy. In addition, the agency recognized that these cases constitute a novel form of human trafficking scheme, connecting forced labor to surrogacy agreements in which female victims are initially provided with enticing living conditions but later subjected to abuse and exploitation.

Even though the country has a number of laws protecting women in both public and private settings, including online and offline ones, this does not guarantee that those who violate these laws will be readily held accountable. Existing systemic inequalities and gender stereotypes have also significantly made women, girls, and sexual and gender minorities—particularly those with multiple intersecting marginalized identities—susceptible to this type of online abuse.

In order to address the dangers and harms facilitated by technology preventing women and other marginalized from engaging in civic, political, and social spheres, there is still a lot of work to do going forward. Users, the government, and platform developers and providers must all work to make sure that even online environments are safe.#

0 Comments