Online Gender-Based Violence in the Philippines | Mid-year Report

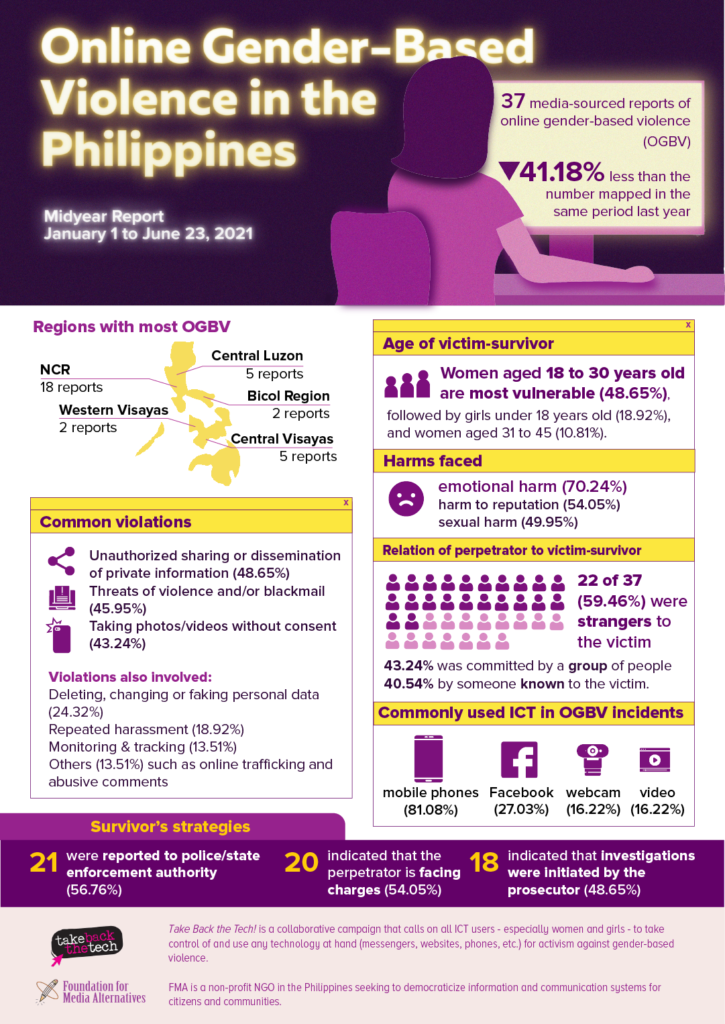

Women and girls’ increased vulnerability to violence also manifested online over the past year. This January 1 to June 23, 2021, FMA recorded 37 media-sourced reports of online gender-based violence (OGBV) with the use of an APC-hosted data mapping platform. While FMA found that the number of media reports went down, the impact of OGBV still remains and cripples Filipino women and girls’ freedoms across offline and online spaces.

Most of the mapped media reports are from the National Capital Region (18 reports), Central Visayas (5 reports), Central Luzon (5 reports), Western Visayas (2 reports), and Bicol Region (2 reports). Victim-survivors reported unauthorized sharing or dissemination of their private information (including private photos or videos of them) (48.65%), threats of violence and/or blackmail (45.95%), and having photos or videos of them without their consent (43.24%). Violations also included:

- Deleting, changing or faking personal data (24.32%)

- Repeated harassment (18.92%)

- Monitoring & tracking (13.51)

- Others (13.51%) such as online trafficking, abusive comments, and accessing private data

Mobile phones (81.08%) were the most commonly used ICT along with Facebook (27.03%), webcam (16.22%), and video (16.22%).

Women across all ages faced some form of violence online, with those aged 18 to 30 years old among the most reported (48.65%), followed by girls under 18 years old (18.92%), and women aged 31 to 45 (10.81%). Majority of the perpetrators (22 of 37 reports or 59.46%) were strangers to the victim, but there were also cases in which OGBV was committed by a group of people (43.24%) and someone known to the victim (40.54%). Multiple manifestations and recurrence of OGBV inflicted psychological toll on women and girl survivors with up to 70.24% of the reports mapped indicated that survivors faced emotional harm, 54.05% faced harm to reputation, and 45.95% faced sexual harm.

Of the 37 incidents, 21 were reported to police/state enforcement authority (56.76%), 20 indicated that the perpetrator is facing charges (54.05%), and 18 indicated that investigations were initiated by the prosecutor (48.65%). Women survivors also confronted their aggressors in 27.03% of the reports. Of those taken to police, 7 reports specified that women were directed to a VAW desk (18.92%). In four reports, women reported the incident to the platform (10.81%).

Perverted persistence

In February 2021, a man was arrested for blackmailing two girls, aged 14 and 18. Jen (not her real name), the older of two, met the man on Facebook and they soon entered into a relationship. He later asked for Jen’s nude photos but when she refused, he came up with edited ones and threatened to post them on social media if Jen didn’t give in. He reportedly went so far as to threaten to kill her younger sister. Jen later decided to seek the help of police and the perpetrator was caught through an entrapment operation.

Sextortion and blackmailing, which are criminalized in the Philippines under the Anti-Photo and Video Voyeurism Act, is among the most persistent cases of OGBV based on FMA’s report mapping. WLB, a feminist legal organization, also reports that the online harassment cases they take (21%), sextortion is among the common violations. From January 2020 to May 2021, 625 voyeurism cases were reported to the Philippine National Police (PNP). However, while there are perpetrators who were lured into entrapment, there are still ones who do not have a name nor face for investigators to begin tracking with. The midyear findings alone reveal that the most of the OGBV reports were committed by someone unknown to the victim (59.46%).

Moreover, perpetrators threatening to post women’s private images online only affirm that perpetrators themselves are aware of pools of voyeurs who are ready to latch on these exploited materials – many of whom seem to be taking shape as digital syndicates for being able to operate networks upon networks under the radar (See: Abuse and anger: inside the online groups spreading stolen, sexual images of women and children). Whether there are successful cases of these non-consensual intimate images (NCII) being removed from the internet remains a gray area, especially that ICT is designed to make it easy for anyone to upload, download, store digital materials, and reach out to their next potential victim.

Targeting the outspoken

Women who are politically active offline are twice as likely to use the internet, as shown by the 2015 findings of Web Foundation. However, in their course of work spanning feminist organizing and journalism, many women activists across the globe have faced some form of ‘digital misogyny’.

In the Philippines, a harassment report involving women’s partylist representative Arlene Brosas, was among those mapped in the first half of 2021. A certain ‘Bishop Bacani’ reached out to her via phone call to inquire about upcoming activities only to later shout, curse, and threaten her with obscene remarks. Upon investigation, the perpetrator turned out to be vlogger Nino Barzaga – the same person behind the harassment of journalist Ellen Tordesillas which happened about a week after Brosas’ encounter.

Ana Patricia Non, a Maginhawa resident who initiated a community pantry, also reported receiving rape and death threats after her number was used in an online food delivery service. Non later halted their operations for a day after seeing a heightened security risk, especially following her and fellow community pantry organizers being ‘unjustly profiled’ by police officers — measures that according to them are supposedly to protect people but which have also met uproar, commotion and fears. Miriam College, an all-female school, also called out the state enforcement’s attention for using a photo of their students in an online forum about the heavily protested Anti-Terror Law.

Visibility is key

PNP reported a declining number of cases of violence against women and children (VAWC) over the years. In the first half of 2021, reports on online gender-based violence in the Philippines are also 41.18% less than the number mapped in the same period last year. Whether there is actually a lower incidence of GBV offline and online is a tricky question especially that the cycle of abuse can immobilize victim-survivors from coming forward. In mapping cases of online gender-based violence, visibility of the incidents is among the challenging parts for generating data. A large proportion of girls who experience online harassment, for instance, ignore their harassers and carry on from the encounter (42%) (p. 32, Free to Be Online Full Report).

The growth of online support for help-seeking victim-survivors over the past year may have been a factor in the low turnout of OGBV reports so far this 2021. Social media posts that criticize mistreatment of women-survivors and call for pro-victim-survivor legislations were at a larger proportion (38%) than posts that display or discuss misogynistic beliefs and attitudes, victim-blaming, or posts involving popular misconceptions (26%). This is also evident in Filipino female students’ continued demand for safe spaces in schools with #FEUHSDoBetter as the latest school-related callout versus sexual misconduct.

These incidents within the first half of 2021 reveal that there should be a consistent shedding of light on OGBV in the Philippines. Online dimensions of violence have to be separately looked into and such data from government agencies and law enforcement have to be regularly updated and made available. Non-profit organizations accommodating abuse reports and cases in the Philippines can also help recognize the role of ICT in VAW across their policy advocacies. Women’s rights advocates, support groups, and online communities, even those that are volunteer-run, are also helpful in tackling GBV by pushing the conversation forward and growing awareness on what victim-survivors have to say about the response and care they need. Platform providers, who take reports from users of community standard violations, can likewise take a more in-depth look into how women’s experience of abuse online can possibly be identified on their platforms. The many languages in the Philippines could also be a barrier in recognizing an incident of OGBV within Filipino communities. Communicating with the victim-survivors or with the peers who submitted a report could be helpful in understanding OGBV in the country.

To provide responses tailored to the OGBV experience, more forms of survivor strategies should also be recognized beyond legal action. When effects of OGBV span moral damages and psychological trauma, what does recovery look like for them? How can different actors support that?

While the internet is a double-edged sword for vulnerable groups to take part in as seen in the persistent cases of OGBV, it can be an empowering tool as well for vulnerable groups to take a hold of. Resources and support for women are being cultivated on growing feminist spaces online. ICT enables women survivors to reach out for help as well. More than just a tool of messaging and exchanging information, the internet has evolved to accommodate various aspects of human lives. There might still be OGBV incidents that are obscure from the eye of the media and authorities. That makes it all the more important to make women and girls understand the technology used against them and shape it as their own kind of weapon in combating manifestations of GBV.

0 Comments