Algorithms of Abuse: Addressing Online Gender-Based Violence in the Age of Artificial Intelligence

As a global leader in social media usage, the Philippines’ environment of pervasive disinformation, paired with a culture of patriarchal gender constructs, foster democratic backsliding and authoritarianism (Kunze et al., 2021). With the country’s low level of media literacy, Filipino people are especially vulnerable to the threats brought by internet communications technologies. Conditions such as this enables people like the former President Rodrigo Duterte to undermine democratic processes and minimize opposition by proliferating fake narratives and information (Kunze et al., 2021).

The emergence of artificial intelligence undeniably presents a double-edged sword across the world. The rapid rise in popularity and widespread nature of various artificial intelligence such as Machine learning (ML), Computer Vision (CV), Fuzzy Logic (FL), and Natural Language has caused a complex set of socio-economic and political disruptions. Such technology also raises growing concerns about fundamental human rights and ethical considerations. Given the lack of transparency in its algorithms, privacy violations, and underrepresentation of marginalized groups in the AI sector are all potential sources of serious harm that, if not addressed proactively, will exacerbate existing inequalities that already disproportionately affect women and girls (Langlois Avocats, 2023).

One of the most serious risks of AI is its ability to facilitate new types of online gender-based violence (OGBV). As AI models enable impersonation, hacking, stalking, and cyber-harassment, the scope and ease with which OGBV is perpetrated expands (Chowdhury & Lakshmi, 2023).

Intersection of AI and OGBV

As AI takes a historical turn in the technological world, it is not only engendering positive outcomes, but also presenting amplified risks, particularly related to OGBV. In fact, as the usage of AI tools increased, violence against women followed this pattern through gender-biased algorithms, cyberattacks, deepfakes, gender disinformation, and so on. According to the Institute of Development Studies, a rise in OGBV ranging from 16% to 58% has been recorded in several countries from 2018 onwards (Hicks, 2021). Unfortunately, this phenomenon affects women, girls, and individuals belonging to the LBTQIA+ community most prominently, and those from minority backgrounds even more. In the Philippines, the journalist Maria Ressa has not been spared of abuse as she faced death threats, doxxing, and rape threats, as well as racist, sexist, and misogynistic abuses online, especially during Duterte’s reign. Her compounding identities as a woman, lesbian, and Filipina further explain the extent to which she suffered as a journalist. Similarly, Maine Mendoza, a Filipinoa actress, and Catriona Gray, the Miss Universe 2018, have fallen victim to deepfakes. Due to the ease at which anyone can access deepfake software within a few clicks, the malicious content can be created and shared at an impressive rate. Technology-mediated offensive acts such as deepfakes cause extensive trauma to its victims as it severely undermines their personhood.

Recommendations

As much as AI can potentially bring harm to women, a lot of entities are trying to tap the potential of AI in helping tech platforms fight against OGBV. For one, Meta aims to develop universal standards to detect any content that is AI-generated images (Clegg, 2024). Twitter, meanwhile, announced that it will be using IBM Watson, an AI that understands nuances in language and intention to identify abuse patterns and prevent them from worsening (Lauder, 2017). However, the fight against OGBV requires cross-platform and global collaboration since tentative solutions to address it present shortcomings at many levels. As modalities of harm incessantly evolving, abusers finding ways to bypass algorithms, and the meaning of phrases shifting based on topical events, it is becoming increasingly difficult to leverage AI for social good (Chowdhury & Lakshmi, 2023). Some initiatives harnessing AI to combat gender inequalities head on include Troll Patrol, Foundation for Media Alternatives, SafeHER, AymurAI, SOF+IA, TARA, WE-Talk project, and many more.

As demonstrated by the array of gender-related laws that exist in the Philippines (e.g., Anti-Violence against Women and Children Act, Safe Spaces Act, Anti-Online Sexual Abuse or Exploitation of Children Act, and Anti-Child Sexual Abuse or Exploitation Materials Act), the World Bank has stated that “the country does not suffer from a lack of good policies to promote gender equality. Where it falls short is in implementing these laws and ensuring that development programs, projects, and activities lead to outcomes that empower women as whole and not just a few groups.” (2020). Thus, greater strides in the adoption, monitoring, and enforcement of policies and programs are vital for solutions proposed by the government, policymakers, and civil society organizations to truly come into effect.

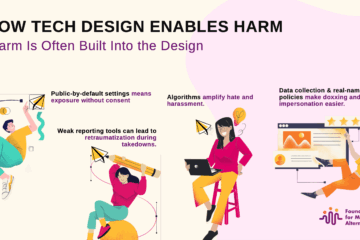

Apart from proper enforcement of laws, technology platforms should also develop an all-encompassing, shared definition of OGBV, track the prevalence of gendered abuse, install a global lexicon repository of gender-related speech, and share the collected data publicly through corporate transparency reports. In collaboration with third-party fact-checking organizations and civil rights groups, they must establish fact-checking networks and image hashing services to put an end to the non-consensual distribution of intimate images, including deep fakes. Meanwhile, governments installing responsive national-level help desks worldwide could bolster the drive to find people who are behind the malicious materials. Additionally, the authorities’ role in mandating algorithm transparency, demanding content moderators to be fluent in all operating languages, and increasing funding towards women-led CSOs and female journalists, especially in authoritarian contexts, is imperative to mitigating AI’s harm. Finally, developing digital tools that adopt “design justice”, “sex and ethics”, and “trauma-informed” approaches while recognizing structural power, positionality, and inequality are crucial to mitigating the dangers of OGBV.

Conclusion

In conclusion, as AI research shows no signs of slowing, we can no longer ignore the plethora of complicated difficulties that such a promising technology presents, particularly in connection to OGBV. Gendered disinformation, cyberattacks, cyber harassment, deepfakes, and privacy violations are examples of OGBV that are extremely harmful to women both online and offline. Before incorporating a technology into a new industry, all stakeholders must prioritize addressing the possible threats of AI and weighing the advantages against its disadvantages. The Philippine government’s commitment to safety must take precedence over its development aspirations, as AI’s contribution to the worsening of OGBV is no longer a novel issue, but one with irrevocable consequences for the lives of society’s most vulnerable citizens.

References:

Chowdhury, R., & Lakshmi, D. (Eds.). (2023). “Your opinion doesn’t matter, anyway”: Exposing technology-facilitated gender-based violence in an era of generative AI. UNESCO. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000387483

Clegg, N. (2024). Labeling AI-Generated Images on Facebook, Instagram, and Thread. Meta, https://about.fb.com/news/2024/02/labeling-ai-generated-images-on-facebook-instagram-and-threads/#:~:text=We’ve%20used%20AI%20systems,(as%20of%20Q3%202023).

Dayrit, M., Nalagon, G. B., Pajo, D. G., Pineda, J. G., Rivera, J. A. (2023-24). Regulating Artificial Intelligence in the Philippines: Policy Paper. Department of Economics at the University of the Philippines Los Baños. https://swisscognitive.ch/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/POLICY-DESIGN-PAPER_AI-GROUP.pdf

Goddard Media LLC. 2024. “Astroturfing”. https://politicaldictionary.com/words/astroturfing/

Hicks, J. 2021. Global evidence on the prevalence and impact of online gender-based violence. K4D Helpdesk Report. Institute of Development Studies. Global-evidence-on-the-prevalence-and-impact-of-online-gender-based-violence-ogbv

Kavanagh, E., & Brown, L. (2019). Towards a research agenda for examining online gender-based violence against women academics. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 44(10), 1379–1387. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2019.1688267

Kunze, A., Schyllander, A., Chambers, K., & Zuroski, N. (2021). Authoritarianism and Gendered Disinformation: A case study of the Philippines. Elliot School of International Affairs, The George Washington University, https://she-persisted.org/Authoritarianism_and_Gendered_Disinformation_May_2021.pdf

Langlois Avocats, 2023. L’éthique en matière d’intelligence artificielle : les biais discriminatoires. Lethique-en-matiere-dintelligence-artificielle-les-biais-discriminatoires

Lauder, E. (2017). Twitter is Using IBM Watson to Fight Online Abuse. AI Business, https://aibusiness.com/companies/twitter-is-using-ibm-watson-to-fight-online-abuse

The World Bank. (2020). Gender-Based Violence Policy and Institutional Mapping Report. https://thedocs.worldbank.org/en/doc/e1575832e43d4030373f9a616975364f-0070062021/original/Philippines-Gender-Based-Violence-Policy-and-Institutional-Mapping-Report.pdf

UN Women. (2022). FAQs: Tech-facilitated gender-based violence. UN Women – Headquarters. https://www.unwomen.org/en/what-we-do/ending-violence-against-women/faqs/tech-facilitated-gender-based-violence

Originally from Mauritius, Carole Babet has made Quebec city her home since 2018. After pursuing sociology studies at Université Laval, Carole started working at l’Engrenage St-Roch which has a mission in improving the quality of life in Saint-Roch, in Quebec city. Carole is sensitive to different realities and life paths of people, and is actively involved in various community projects. She continues to be involved, hoping that everyone, regardless of their age, gender, sexual orientation or origin, inter alia, can find their place in an inclusive, caring and just society. During this summer, through the International Youth Internship Program of Alternatives, she had the opportunity of interning in the gender program at Foundations for Media Alternatives in Quezon City.

Celine Li is an Economics, Sociology, and Political Science undergraduate student attending McGill University located in Montreal, Canada. Striving to contribute to initiatives that advocate and support for greater representation of marginalized voices, she had the pleasure of interning at Foundations for Media Alternatives in Quezon City this summer through the International Youth Internship Program, offered by the Montreal-based NGO, Alternatives.

This is an output from FMA’s interns. The views and opinions expressed by the hosts do not state or reflect those of the organization.

0 Comments