FMA welcomes the filing of Senate Bills 180 and 1251

Pasay City – The Foundation for Media Alternatives (FMA) was invited by the Senate Committee on Women, Children, Family Relations and Gender Equality as one of the resource persons during the second public hearing on Gender-based Electronic Violence (SBN 1251) and the E-VAW Law of 2016. The Public Hearing was presided over by Senator Risa Hontiveros, Senate Committee Chair on Women, Children, Family Relations and Gender Equality.

Below is the full statement of the organization during the Public Hearing:

“Thank you Madam Chair for inviting the Foundation for Media Alternatives or FMA to this public hearing.

FMA welcomes the filing of Senate Bills 180 and 1251.

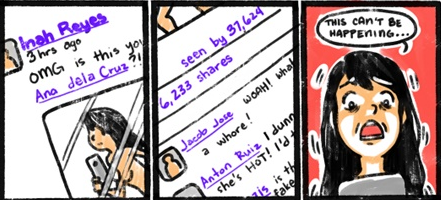

For the last several years, FMA has been doing work to raise awareness on the issue of electronic violence against women or EVAW. We have been involved in multi-country researches that looked into and analysed EVAW, did a few case studies, and have mapped cases of online gender-based violence since 2012 to the present, based on media reports that we have monitored, as well as cases reported to us by our partners and other individuals. In the last 12 months, we have also monitored several cases of online harassment targetted at women who have been vocal about their political stands or advocacies. Some women have even been threatened with rape and even death.

‘Online abuse and gender-based violence’ refers to a range of acts and practices that either occurs online, or through the use of information and communications technologies. It falls within the definition of gender-based violence under General Recommendation 19 of the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) convention; that is, “violence that is directed against a woman because she is a woman or that affects women disproportionately. It includes acts that inflict physical, mental or sexual harm or suffering, threats of such acts, coercion and other deprivations of liberty.” This is the basis of the definition of VAW that was adopted in RA 9710 or the Magna Carta of Women.

Recognising the rapidly changing landscape of information and communications technologies that affect the expression of such abuse and violence, this definition is not exhaustive or definitive, but rather facilitative.

While violations of users’ rights online may affect all users in differing ways, incidents of online abuse and gender-based violence rest on existing disparity and discrimination. Gender-based violence is a “manifestation of historically unequal power relations between women and men, which have led to domination over, and discrimination against, women by men and to the prevention of the full advancement of women”.

Electronic violence against women and online gender-based violence are part of gender-based violence. In addition to existing structural inequality and discrimination between genders, disparity in access to, participation in and decision-making over the Internet and technology development are all factors that play a part in its manifestation online and through the use of information and communications technology (ICT). As such, online abuse and gender-based violence disproportionately affect women in their online interactions; encompassing acts of gender-based violence such as domestic violence, sexual harassment, sexual violence, and violence against women in times of conflict, that are committed, abetted or aggravated, in part or fully, by the use of ICTs.

The UN HRC consensus resolution The promotion, protection and enjoyment of human rights on the Internet affirmed that the same rights that people have offline must also be protected online.11 There are also numerous international human rights instruments and documents that state clearly that all forms of gender-based violence amount to discrimination, and seriously inhibit women’s ability to enjoy their human rights and fundamental freedoms.

This includes acts of gender-based violence that are experienced online or expressed through the use of ICTs.

Women do not have to be Internet users to suffer online violence and/or abuse (e.g. the distribution of rape videos online where victims are unaware of the distribution of such videos online). On the other hand, for many women who are active online, online spaces are intricately linked to offline spaces; making it difficult for them to differentiate between experiences of events that take place online versus events offline events.

The following are our comments on the bills:

1. On Section 3 (e) of SB 180 on the Definition of electronic violence against women (eVAW), to consider the following types practices that may constitute forms of online abuse and/or gender based violence: infringement of privacy, damaging reputation and/or credibility, direct threats and/or violence, –/ These acts are often an extension of existing gender-based violence, such as domestic violence, stalking and sexual harassment, or targets the victim on the basis of gender or sexuality.

2. Section on Electronic Protection Orders (present in both SB 180 and SB 1251). When issuing a temporary protection order, there is the presumption that the perpetrator of the violence is known. But in cases of online VAW, that is not often the case. The perpetrator may be anonymous, or may not be living in the Philippines. In such cases, to whom and how does the Barangay or the Court issue the protection order. There may be a need to further look into its feasibility, considering that we are dealing with technology.

3. On the composition of the IACVAW. Replace the Department of Science and Technology with the Department of Information and Communications Technology.

4. Section 6 of SB 1251 on Mandatory education against gender-based VAW. If there will be such, then teachers should undergo training on how to teach students about gender-based VAW.

We also propose the training of law enforcers and judges on the issue. This would include gender-sensitivity trainings, as well as knowledge on how technology works and its nexus with VAW.

When developing legislative responses to the issue, it is important that relief and redress be prioritised over criminalisation. Not only do governments need to prioritise the access that victims and survivors of online abuse and gender-based violence have to justice, but flexible and informal (yet also transparent) measures that can more easily, quickly and effectively respond to online behaviour need to be investigated.

Thank you.”#

0 Comments