Online Gender-Based Violence in the Philippines: 2023 Yearend Report

Violence against women and girls is an alarming issue that occurs within and beyond the online sphere. The rapid evolution of technology may often mean progress and convenience, but existing digital tools have also lent themselves to the proliferation of online gender-based violence (OGBV).

Though violence targeting one’s gender is not a new phenomenon, new technology has given rise to new and heightened forms of OGBV. This comes in various methods, as in cyberstalking, doxxing, sextortion, non-consensual distribution of intimate images, among others, that poses serious threats to women’s safety and well-being.

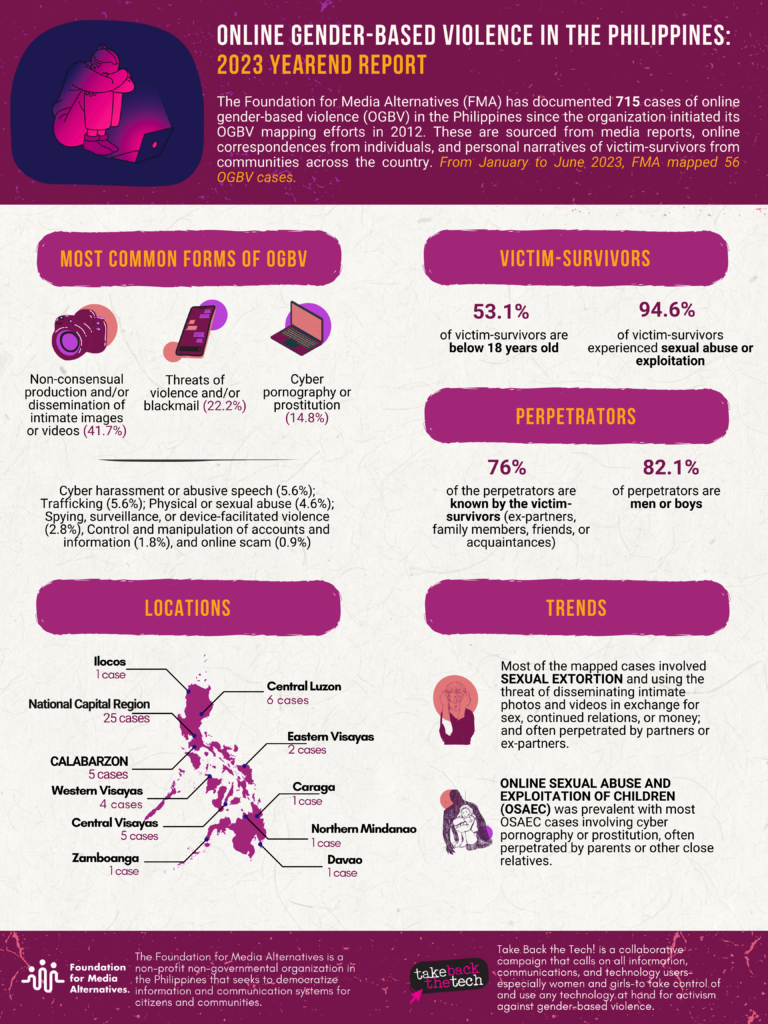

As part of its advocacy to build a safer Internet, the Foundation for Media Alternatives (FMA) initiated an effort to map OGBV cases in the Philippines in 2012 which continues up to present. From January to December 2023, FMA mapped a total of 56 OGBV cases and determined the most common forms and manifestations of OGBV:

- Non-consensual production and/or dissemination of intimate images or videos (41.7%)

- Threats of violence and/or blackmail (22.2%)

- Cyber pornography or prostitution (14.8%)

Other offenses include cyber harassment or abusive speech (5.6%); trafficking (5.6%); physical or sexual abuse (4.6%); spying, surveillance, or device-facilitated violence (2.8%), control and manipulation of accounts and information (1.8%), and online scams (0.9%).

The locations with the most OGBV cases are the National Capital Region (25 cases); Central Luzon (6 cases); CALABARZON (5 cases); and Central Visayas (5 cases). Other regions with mapped cases include Ilocos (2 cases), Western Visayas (4 cases), Eastern Visayas (2 cases), Zamboanga (1 case), Northern Mindanao (1 case), Davao (1 case), and Caraga (1 case). There have also been reports of OGBV by perpetrators based overseas (3 cases).

The victim-survivors in the mapped cases are all women and girls with the majority being below 18 years old (53.1%). Other victim-survivors are 18 to 30 years old (10.9%), 31 to 45 years old (4.7%), 46 to 60 years old (3.1%), over 60 years old (1.6%), and of undisclosed legal age (26.6%). Out of the documented cases, 82.1% of the perpetrators are male and 17.9% are female; while 85.4% are known by the victim-survivors and include partners/ex-partners (45.8%), parents (20.8%), other relatives (6.2%), friends (10.4%), or workmates (2.1%).

It is important to note, however, that these numbers do not paint a complete picture of OGBV cases in the Philippines as many stories often go unreported. For one, the victim-survivors’ fear of social sanctions prevents them from sharing their stories. The normalization of violence within households and the lack of mechanisms to access justice also dissuade women and girls from holding perpetrators to account. There is also the persistent culture of victim-blaming and overall misogyny which can quickly discount the victim-survivor’s experience and shame them for speaking up.

With this kind of unsupportive environment, OGBV cases can easily go rampant. In September 2023, the Cybercrime Investigation and Coordinating Center (CICC) reported that the Philippines ranked second worldwide on online sexual abuse and exploitation of children (OSAEC). Young girls, particularly those who belong in poor communities, are the most vulnerable to different forms of exploitation whether in digital or physical spaces.

This is evidenced by the prevalence of the mapped OSAEC cases that involve the production of materials for cyber pornography and prostitution. Minors as young as three years old are coerced to engage in sexual acts that are captured on photo or video and posted online for public consumption or are sent directly to individual viewers. Oftentimes, perpetrators are directly related to the victim-survivors such as parents or close relatives who sell these materials for economic gain.

A US Navy ship contractor from California was sentenced to 50 years in prison for producing child pornography and transporting the materials to the US. The perpetrator met two Filipina women through an online chatroom whom he paid a monthly fee to help him exploit victim-survivors between the ages of four and 13, including the children of one of the women. An examination of the perpetrator’s computers, mobile phone, and other electronic devices revealed that he had produced 340 videos and 650 images of his abuse of young girls.

Some accounts from the mapped OGBV cases for 2023 are detailed below:

In Paranaque City, a 28-year-old man hacked his ex-girlfriend’s e-mail and Facebook accounts and promised to give her the new passwords if she agreed to meet up. When the two met, the perpetrator drove the victim-survivor to a motel and coerced her to drink alcohol in exchange for the passwords that she later discovered did not work. The perpetrator demanded to meet again and threatened to post her intimate photos online. Following the perpetrator’s arrest, videos of the victim-survivor being abused were found on his phone.

In Cebu City, a 32-year-old man threatened to display tarpaulins with intimate photos of his ex-girlfriend and screen captures of conversations between the victim-survivor and her alleged “lover” that were taken by the perpetrator from the victim-survivor’s mobile phone. The perpetrator intended to put these tarpaulins up at the victim-survivor’s places of work and residence to blackmail her into continuing their relationship after not having agreed with her decision to break up.

In Tarlac City, two men coerced a minor to send intimate photos and videos to which the victim-survivor complied out of fear. When the victim-survivor refused to continue sending, the perpetrators created a Facebook account, publicly posted the sensitive materials, and asked the victim-survivor to meet up with them in exchange for the deletion of the photos and videos.

Aside from the actual violence that comes with being sexually abused and exploited, the technological aspect of OGBV is also being used to further traumatize women. Many digital spaces conveniently allow for the non-consensual dissemination of intimate media and for these materials to possibly exist on various sites and channels perpetually.

Though there are laws in place to combat OGBV such as RA No. 11313 or the Safe Spaces Act; RA No. 10175 or the Cybercrime Prevention Act; and RA No. 9262 or the Anti-Violence Against Women and Their Children Act, these policies cannot take full effect given the pervading culture that hinders women from telling their stories.

Given the various factors affecting the documentation and resolution of OGBV cases, it is evident that there is a lot of work that needs to be done to protect women and girls from this threat. We can push for effective implementation of laws against OGBV or call for social media platforms to have better policies in terms of protecting women and girls online. But we can also build networks that can empower victim-survivors to share their experience and help them access much deserved justice.

0 Comments