Philippines

By Philip Arnold Tuaño, Christina Lopez and Kenneth Reyes[1]

I. Introduction

The Open e-Governance Index (OeGI) is an action-research project that aims to develop a quantitative tool to gauge the state of e-governance around the world. It builds on an earlier effort by the Foundation for Media Alternatives (FMA) to develop and popularize an “Open eGovernance Index” which hopes to be a normative tool for assessing how countries are utilizing openness in network societies to enhance public service, citizen participation/engagement, and addressing communication rights[2]

The objectives of the Open e-Governance Index project are to: (a) further understand democratic e-governance, particularly through developing the discourse of “Open E- Governance”; (b) help develop policy on ICT and governance; and engage policy stakeholders directly, around the notions of “Open Governance”; and (c) develop a concrete resource for citizens/individuals, groups/non-government organizations to engage the policymakers on “Open E-Governance”. The index will measure five dimensions, which include meshed eGovernment, eParticipation channels, universal access/digital inclusion, civil society use of ICTs, and fostering an enabling environment for open eGovernance.

OeGI in this current phase is being piloted in five countries— Colombia, Indonesia, Pakistan, the Philippines and Uganda—all with differing levels of socio-economic development and state of infrastructure and policy of ICTs. These countries were chosen because of the apparent diversity of appreciation of ‘eGoverance’ and ‘openness’ not only among their governments but also across their civil society sector. A framework, based on earlier work in the first phase of implementation in 2011- 2012, was revised and a methodology (mainly using secondary data to fill-up a score sheet; this was also validated among key experts across society) was adopted for use in this round of implementation.

The FMA undertook the research and drafting of this OeGi report for the Philippines during the November 2016 to April 2017 period; the research was undertaken utilizing secondary data research and several focus group discussions. The study also was enhanced by several studies that the FMA had undertaken in the areas of internet governance, privacy rights and gender aspects of ICTs. This is the second iteration of the OeGI implementation in the country; the first report was undertaken by the School of Government, Ateneo de Manila University, in November, 2011 (and finalized in March, 2012)[3].

The report will provide an overview of the country, then discuss the situation of open eGovernance in the Philippines by discussing the rating given to each indicator. Then a discussion will be undertaken to assess the state of openness and eGovernance in the country and provide a few policy and programmatic implications, and finally, a conclusion will cap the findings made by this study.

II. Country Context

Introduction. The Philippines is an archipelagic nation composed of more than 7,000 islands located in southeast Asia. Although the Philippines’ aboriginal inhabitants arrived from the Asian mainland around 25,000 BC, followed by waves of Indonesian and Malayan settlers from 3000 BC onward, as a geographic entity, it was formally constituted by Spanish colonizers was established in the 16th century. After the 1898 War of Philippine Independence, the archipelago was occupied by its erstwhile ally the United States of America. American-inspired democratic institutions were imported into the country, including free press, a bicameral Congress, and, an executive headed by a president, as formalized in the 1935 Constitution.

After World War II and a period of brutal Japanese occupation, the country received its independence from the U.S. and the Republic of the Philippines was born in 1946. Two political parties, the Nacionalistas and the Liberals, competed in a boisterous democracy until Ferdinand Marcos declared martial law in 1972 and forced the passage of a new constitution through referendum. Marcos remained in power for another 14 years, and his administration was marked by media control, enforced disappearances, and stifling of political and social dissent. The death of the popular senator Benigno “Ninoy” Aquino which galvanized popular opposition against the regime and the defection of Marcos’ army and police chiefs led to the bloodless People Power Revolution in 1986, deposing the dictator and returning the country to democracy.

Political freedoms and freedom of the press. The 1987 Constitution formally guarantees freedoms of expression and press. Today, the Philippines enjoys a vibrant and outspoken media, though prone to sensationalism at times. There are more than sixteen national broadsheets, including those printed in the English, Filipino and Mandarin language, while there are more than 20 national tabloids that exists competing for the general public’s attention; at the same time, there are dozens of community newspapers that exists around the country. While government censorship is not generally an issue, the 2007 Human Security Act allows wiretapping of journalists based on suspicion of terrorism. At the same time, libel continues to be a criminal offense and journalists continue to face prosecution in courts due to this; however, there are very few convictions and thus libel continues to be a means of harassing journalists[4].

One of the disturbing trends since the advent of democratic restoration has been the killings of journalists in the country. The Committee on the Protection of Journalists, an independent watchdog group that monitors press freedom around the world, has reported that more than 78 journalists have been killed in the country since 1992[5]. Some of the more gregarious cases have been the killing of the radio commentator Jun Pala in Davao city in 2003 due to his criticism of extra-judicial killings, the assassination of the Dr. Gerry Ortega, a known environmental crusader in Palawan province, the death of journalist Mel Magsino, an investigative reporter who had filed reports on local corruption, and Todoy Escanilla, also a member of a human rights group in Bicol region.

Freedom of religion and academic freedom are generally recognized. Citizen activism is robust although there are cases of harassment of specific groups. Democratic competition remains open though as boisterous as ever, with politicians divided by kinship networks and personal alliances rather than political ideologies. Individuals generally have access to the internet is widely which is widely available; in fact, the internet has seen the growth of alternative news sources including web-based news sites, which have been increasingly been popular among Filipinos. However, there are cases in which the journalists in these news sites have been prosecuted under the 2012 Cybercrime Act, which allows limited liability for online libel attributed to the original author.

The past few years saw the rise of “alternative” media sources in the form of blogs and other social networking platforms, whose quality and accuracy varies wildly[6]. This trend accelerated during and after the 2016 elections. As more people turn to these for their information, traditional media with established vetting processes are quickly losing relevance, allowing dubious materials or “fake news” to increasingly influence policy debates. These type of materials create a false sense of reality for the unwitting public, and leads them to accept the untruths as certainty. This erodes the importance of the free press to serve as an effective watchdogs of government action given that more and more public have been accepting of this mode of information.

Generally, there is freedom of association and demonstrations against the government are normally allowed, although many restrictions have been placed on these. Nevertheless, the country hosts numerous civil society organizations, including non-government organizations, people’s organizations, trade unions, cooperatives and economic unions. The Securities and Exchange Commission, the government agency in which non-stock, non-profit organizations have to register, estimates that there are more than 100,000 of this type of groups in its database. Trade unions have to register with the government’s Department of Labor and Employment and less than 10 percent of industrial workers have been unionized.

Political and economic situation. National and local elections have continuously been undertaken since 1987. The Philippines successfully held national elections last May 2016, with Davao mayor Rodrigo Duterte winning as President and Camarines Sur representative Leni Robredo winning as Vice-president. A “supermajority” bloc, composed of legislators from a wide spectrum of political parties and allied with the President was formed in Congress, although several senators recently bolted the supermajority in the Upper House last February. As of early 2017, the administration party is the Partido Demokratiko Pilipino- Laban ng Bayan, chaired by the leader of the Senate, while main opposition party is the Liberal Party, who counts the Vice President as its chair. Village elections, scheduled in the latter part of the year, will be most likely postponed.

President Duterte is widely described as a populist leader with authoritarian leanings. Among his first acts in office was to initiate a vigorous war on drugs through the Philippine National Police, which, though popular, has invited strong criticisms from both the domestic opposition and the international community for alleged human rights violations. After just six months in office, it has been estimated that more than 7,000 persons have been killed due to anti-drug operations[7].

However, President Duterte has been able to capitalize on his popularity by maximizing support from various political element in the country; his cabinet, meanwhile, is a curious mix of populists, conservative businesspersons, members of the extreme left, and long-time associates from Davao city. The Duterte administration has shown little patience for democratic processes, with the President making numerous off-hand remarks indicating his preference for authoritarian rule. However, there is growing opposition to his administration due to the anti-drug policy and the fact that he has allowed a former Philippine dictator, Ferdinand Marcos, to be buried in the country’s heroes’ cemetery last February. Also, Church has been particularly opposed with the number of bills that aim to re-introduce the death penalty and to reduce the minimum age of criminal responsibility of children to nine years old.

In terms of economic growth, following years of successive increases in the gross domestic product, the National Economic and Development Authority (NEDA) has laid down a blueprint to achieve a predominantly middle-class country by 2040. To this end, members of the present administration have pushed for tax reforms to finance an ambitious infrastructure spending program. There are proposals to further relax the country’s foreign investment restrictions and to jumpstart an industrialization development program, which already has started in the automobile manufacturing sector.

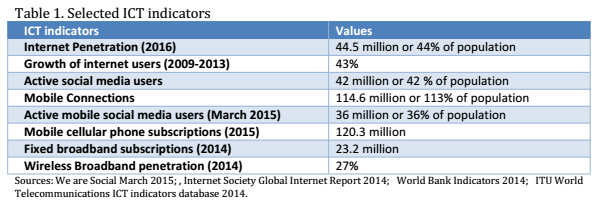

State of Information and Communications Technology. The use of mobile and broadband internet has been gaining widespread use in the country. According to international statistics on information and technology use, the Philippines has around close to 45 percent internet penetration rate, which means that around 45 million individuals have been accessing the web. This has been largely driven by the growth of mobile telephony; it has been estimated that there are more than 120 million cellular phone subscribers, which is more than the number of individuals in the country.

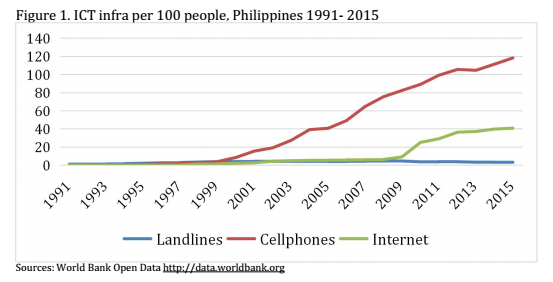

The growth of ICT infrastructure, especially cellular phones, have been large. Year on year growth since the advent of mobile phones has been 40 percent per year, although the grown rates in the past five years has been less than seven percent per annum. On the other hand, the number of internet users per 100 people has increased from 5.4 in 2005 to 40.7 in 2015. See Figure 1 below:

However, this growth in ICT access and use belies large sub-national differences. According to Astrologo, Bulan and Catalan (2016), access to ICT infrastructure shows that it is concentrated in two main regional centers- Metro Manila and the Metro Cebu areas, On the other hand, internet access is available only mainly also in the former and other surrounding politico-administrative regions.

The growth in ICT use and access has happened even though the telecommunications industry remains a duopoly dominated by Smart (owned by PLDT Inc.) and Globe (owned by Ayala Corp). Several legislative initiatives in the 1990’s, including Executive Order 109 in 1992 and the Public Telecommunications Act or Republic Act 7925 of 1992, which require telecom operators to interconnect and provide service to underserved areas, which attempted to increase competition in the industry has not borne long-term results. The Department of Information and Communications Technology (DICT) and the National Telecommunications Commission (NTC) are the main government agencies supervising the industry.

The conglomerate San Miguel had attempted to enter as the third player in the industry. However, after failing to secure a foreign partnership in 2016, it eventually sold its telco assets to Smart and Globe in a deal that attracted the scrutiny of the newly created Philippine Competition Commission (PCC), which is the country’s competition watchdog. Currently, the PCC has ruled that the deal is “anti-competitive”[8] and there are talks of requiring the buyers to divest their telecom assets, including ownership of specific radio spectrum, before the deal is approved.

According to the Foundation for Media Alternatives (2016), there are several issues that have affected access and use of ICTs. These include:

- The lack of meaningful ICT access despite growth, especially in rural areas, which can be traced to the lack of a well-articulated and strategic universal access strategy for the country, and the absence of a national digital literacy, of which there is also no articulated framework yet;

- Increasing complexity of ICTs in which government policies have not coped with; the government is debating, for example, whether to regulate social media, which have been the primary gateway for Filipinos to utilize the web;

- Gaps in ICT policy leadership and weak capacity of state agencies in implementing policies and regulations; government’s previous ICT development plan have not been fully embraced within the bureaucracy, while important policy inputs have been unarticulated and languished; at the same time, there is a general lack of coordination between ICT agencies and other government agencies that oversee internet rights and legislative development;

- Lack of meaningful civil society consultation; there is no structure nor mechanisms that allow for widespread participation of civil society groups in providing inputs to policies and regulations.

In general, it can be said that a liberalized telecommunications and Internet environment has been a major factor in the increase access to communication technology for a large segment of the Philippine population; data shows that this is concentrated in the main urban centers of the country. However, this private sector-led market environment coupled with weak regulatory institutions have resulted in in the dominance of large corporations, which when coupled with a weak regulatory framework, has exposed serious gaps in protecting consumers and defending the liberties of the general public to be able to access communications.

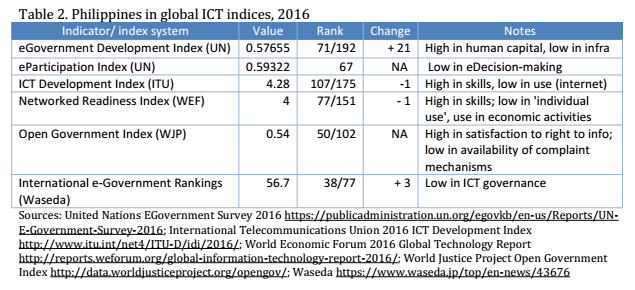

Philippines in global ICT indices. According to various ICT indices (see Table 2 below), the Philippines generally ranks well in terms of skills and human capital development, but low in general state/use of ICT infrastructure. The eGovernment Development Index, ICT Development Index and the Networked Readiness Index, produced by the United Nations, International Telecommunications Union and the World Economic Forum, respectively, shows that the Philippines ranks high in terms of human development; however, access to infrastructure, including mobile telephony and internet, remain low compared to the progress made in other countries.

On the other hand, while the country ranks generally high in terms of access to information from the government (at least compared to other countries), it has ranked generally low in terms of the availability of mechanisms in complaining to the government. Thus, in general it can be stated that the Philippines is generally in the middle tier/ rank in terms of these different ICT indices.

III. Framework and Process of Implementation

Given the situation in the Philippines, the question is now how to assess the country’s performance in evolving two areas- ‘eGovernance’ and ‘openness’. eGovernance is defined as a series of activities composed of coordinating, arbitrating, networking and regulating with and of ICTs, by the state, but also by non-state actors, including business, civil society and communities. On the other hand, openness can be understood as transparency of public action to the general public. These are norms by which states—as well as non-state actors–seek to extend traditional notions of democracy and visions of development.

These concepts go beyond the traditional understanding that the use of ICTs (now including social media) as delivery mechanisms for public goods., and that openness signifies transparency of public actions to the public. This notion of ‘open eGovernance’ therefore highlights the importance of participation of different actors (including media, NGOs/POs, academe, and others) and also as a means of information sharing, citizen/public engagement, and even policy development/rulemaking. At the same time, this concept leverages the benefits of new social technologies and innovative ICT applications to deepen democracy.

To test these notions on a country basis, a scorecard was developing assessing the state of eGovernance in a nation in terms of undertaking a series of activities composed of coordinating, arbitrating, networking and regulating with and of information and communication technologies, not only the state, but also non-state actors, including business, civil society and communities, and is specifically evaluated in terms of five dimensions:

- Meshed eGovernment – the ability of governments to provide citizen centric online services.

- eParticipation Channels –the use of new, digital medium for public participation.

- Digital Inclusion – the presence of policies and programs that supports the public’s wider use of the ICTs

- ICT-empowered Civil Society – the ability to which non-state political actors use ICT to promote their interests

- Open Legal and Policy Eco System – the extent of the access of the general population to information and knowledge and recognition by the government to foster the right to free expression, right over personal communication, cultural freedom, and the use of local languages.

The Foundation for Media Alternatives undertook the process of implementation of the Open eGovernance Index country report for the Philippines. The process of implementation was undertaken during the November 2016 to March 2017 period.

A review of secondary data from November 2016 to March 2017 in which information on the different indicators are reviewed using a web search and review of documents. The FMA also undertook two country validation workshops- one in January, another in February; but while there was some difficulty in getting the targeted informants in the meeting, there was a very good exchange of information. Representatives from the civil society comprised most of the attendees in the first workshop, while the second workshop was composed of representatives coming from various government agencies.

To provide information on the civil society access to ICTs, a survey of around fifteen organizations was undertaken on the perception on their use of ICTs.

IV. Discussion of Results

Dimension 1: Meshed eGovernment

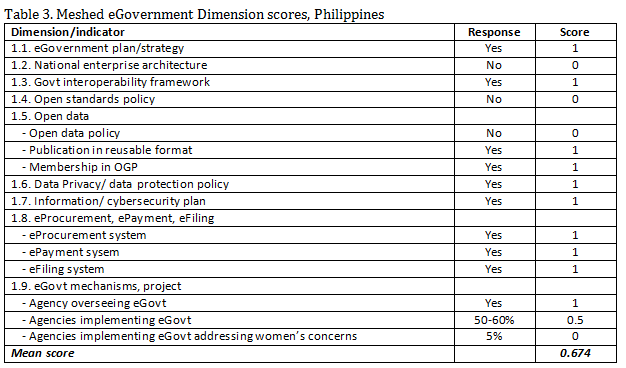

This dimension pertains to the government’s policies and practice in the use of ICTs in its internal or in-house operations and its ability to pull together different agencies under a common interoperable framework within which agencies can share data in an efficient manner. Primarily, this dimension is designed to measure how well and how much a government utilizes ICTs. The scores for the Philippines can be found in Table 3 below.

In terms of ICT governance structures, the Department of Information and Communication Technology (DICT) was created under Republic Act 10844 and was signed into law in May, 2016. The law provides that the DICT be the highest policy-making executive body in terms of policies and regulations related to ICTs, develop frameworks for the identification and prioritization of eGovernment policies, prescribe rules to widen access in underserved areas and provide free access in public offices and harmonize all ICT plans and initiatives. The DICT took over functions of the Information and Communication Technology Office under the government’s Department of Science and Technology.

A head of agency with Cabinet rank was appointed upon the assumption of a new government in June, 2016, and the agency personnel are being filled, although the senior staff have been appointed. Other offices integrated in the agency integrated with the office are the National Computer Center, the government central ICT agency, the National Computer Institute and the National Telecommunication Training Institutes, both training centers and the Telecommunications Office, which formerly operated the telecommunications network of the government.

The National Telecommunications Commission, the telecoms regulator, has been retained as a separate agency from the DICT. A National Privacy Commission has also been created to monitor data privacy issues, and this is also separate from the DICT.

In terms of eGov plans, the DICT oversees the implementation of the eGovernment Master Plan/ Philippine Digital Strategy, which is the “blueprint for ICT integration” in the bureaucracy, but this program ended in 2016, and the DICT is in the process of creating a new ICT plan[9].

While there is no national enterprise architecture plan (an attempt has been undertaken draft government common platform plan created by the Advanced Science and Technology Institute), a government interoperability framework has been written and after several rounds of consultation has been undertaken in 2013, is currently being implemented. The Philippine eGovernment Interoperability Framework enables data and information exchange and reuse among government agencies, and consists of three parts: technical aspects and interoperability standards, information interoperability and exchange and business process interoperability[10].

Legislation has still been pending regarding the adoption of open standards; more specifically, several bills been filed in the previous years for the national government to undertake this policy. In the current 17th Congress, a bill has been filed promoting the development and use of free and open source software, as of this writing, the bill has been referred to a committee in the Lower House[11]. The Bureau of Product Standards of the government’s Department of Trade and Industry has been examining the adoption of open standards for software in the country; consultations have been undertaken with trade and consumer groups[12].

There is a Joint Memorandum Circular No. 2014-01 that aims to inform agencies of the Open Data Philippines (Open Data) and the roles and responsibilities of each agencies across the bureaucracy, state educational institutions and government-owned corporations; other government entities such as the Congress, the Supreme Court and other judicial bodies have been encouraged to participate[13]. A task force on open data, which includes the presidential spokesperson’s office, the budget and management department, and the presidential communications strategy has been organized last January 2014. In July 2015, the task force released guidelines on open data implementation under Joint Memorandum Circular No. 2015-01; the rules follow a provision of the 2015 national budget[14].

In terms of data dissemination, many government agencies, especially related to statistical data collection and dissemination, have been publishing data in reusable formats. This includes the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (BSP), the Department of Finance (DoF) and the Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA), which are the main providers of government data in the country. There is an open data portal but the guidelines for disseminating and maintaining the portal has to be developed and, at the same time, most of the data has to be published in a reusable

Under the new Duterte administration, the direction of open data policy is unclear; the DICT should create guidelines on open data dissemination. But the government has been able to issue a freedom of information (FOI) order[15]; there is already in existence a portal for all FOI requests made by the general public[16].

Also through the task force, the country is one of eight countries that participated in the founding of the Open Government Partnership, which has been established as the global network which has been pushing greater transparency in public information The country has committed to three action plans and 40 commitments as a member of OGP[17]; it has also convened a multi-sectoral partnership to support implementation of the country’s plans. Under the current plan, three new commitments are being adopted, including an ‘anti-red tape’ program, the implementation of a local government competitiveness index and the implementation of a community driven poverty reduction program.

On data privacy, the National Privacy Commission (NPC) has been established by virtue of Republic Act No. 10173 also known as the Data Privacy Act of 2012, which seeks “to protect the fundamental human right of privacy, of communication while ensuring free flow of information to promote innovation and growth”[18]. In September 2016, the NPC finalized the implementing rules and regulations for undertaking the provisions of the law[19].

The NPC is currently disseminating a data privacy policy[20] which establishes the requirements for the collection, access, use, dissemination and storage of personal and sensitive data; as of writing, (NPC has issued memorandum circulars on Security of Personal Data in Government Agencies, Data Sharing Agreements Involving Government Agencies, Personal Data Breach Management and Rules of Procedure[21] ) It has been undertaking orientation seminars for data privacy officers across the government bureaucracy.

A national cyber security plan has been created to address critical infrastructure protection concerns; this was disseminated last December, 2016, and mandates the implementation of resiliency measures to improve the ability to respond to cyber threats and to implement an awareness campaign on cybersecurity[22].

An eProcurement program has been in place since the early 2000s; the Government Procurement Act prescribes the necessary rules and regulations for the modernization of procurement activities of the bureaucracy. A web portal called Philippine Government Electronic Procurement Service or PhilGEPS[23] has been established as the primary information, including the list of authorized vendors, which all government agencies are mandated to utilize.

On the other hand, guidelines have been disseminated by the Department of Trade and Industry and the Department of Finance in 2006 for the implementation of an electronic payment and collection system for payment of fees and charges due to the government[24]. A more recent order by the same agencies lays down guidelines for electronic payments, including credit and debit cards, for government transactions; these guidelines are under the framework of a government law, the eCommerce Act of 2000, which recognizes the use of electronic payment systems in various types of transactions. As of writing, the Bureau of Internal Revenue, the government’s revenue collection agency, utilizes such a system for payment of corporate taxes[25].

Various efiling systems have been created across the government bureaucracy. The Supreme Court, the highest judicial body in the country, for example, allows petitioners to submit electronic copies of all pleadings filed with the body[26]. The PSA, which is also the central civil registry, also has a facility for submitting requests for birth, marriage and death certificates[27]. The national government portal, a single window containing all online information on government’s public services, which is being set up also will provide access for citizens to apply for a drivers’ licenses, to file taxes and to renew their passports.

There are many Cabinet level agencies that are undertaking eGov projects but their success is also uneven. A review of eGovt projects being undertaken by the various national government agencies show that around half of all Cabinet level agencies have been undertaking large programs; the other half have been undertaking projects but these are on a very small scale (i.e., improvement of their web interface). Also, very few Cabinet-level agencies have been developing eGovt projects that specifically benefit women, and there are recommendations to strengthen the linkages of government agencies with women’s online concerns[28].

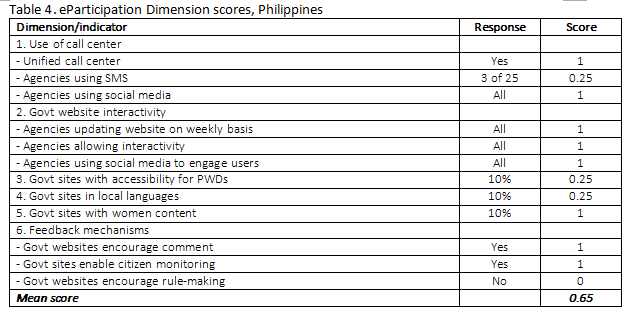

Dimension 2: eParticipation

This dimension looks at whether new ICT channels are being made available to citizens for use in: (1) obtaining information from and about government; (2) share/express their views with decision makers or policy makers; and (3) collaborate in governance. This dimensions intends to convey how well and how much the government utilizes ICT to communicate and interact with its citizens. The scores for the Philippines are as follows:

In terms of the presence of a centralized call center, a recent government order provides for the use of 911 and 8888 as the national emergency and citizen complaint hotline numbers, respectively.; the development of center that can distribute public calls to relevant government agencies still has to be developed. An existing emergency line will be rerouted to the new number, while the citizens’ complaint number will be supported by a national contact center that is being organized by the Civil Service Commission and the National Computer Center of the DICT.[29]

However, the issue is whether specific government departments can support this centralized number and contact center. Out of 25 selected Cabinet-level offices, only more than half (or 14 agencies) have working trunk lines, which connect the department central office to their units.All Cabinet agencies have social media accounts, shown by the Facebook or Twitter handles these agencies show in their websites, while other agencies can also be connected to their accounts in Instagram, Youtube and Google+. A smaller number of agencies link their department heads cabinet-level officers to their Facebook and Twitter accounts. However, only a handful (the Department of Trade and Industry, Department of Environment and Natural Resources, and the Department of Education) have centralized short messaging systems.

All government agencies have centralized websites; in the previous administration, web template guidelines have been issued as part of a memorandum circular which also provides rules for web hosting services that is undertaken by the government’s science and technology department. The guidelines also mandate the use of a transparency seal and pledge of commitment by the government agencies to create an interface for feedback and comments on the implementation of projects and plans[30]. However, it is not clear whether this will be taken up again by the current dispensation.

The agency websites are written primarily in English, one of the official languages of the country. However, some of the contents of the sites are written in Filipino, the other official language; regional languages are at times used in the websites of the units of government agencies that focus on specific sub-national administrative regions. The government’s commission on the Filipino language and the presidential office on communications strategy have formulated guidelines on the use of local languages on the web.

There is also a plan to develop a national government portal (NGP)[31] the give its citizens faster, more reliable and easier access to information and services. The DICT through iGovPhil project, the NGP will serve as a one-stop shop of all government services to the public sector and private businesses. The NGP will serve as a single window containing all online information and operational infrastructures, and public services of the government. The single portal will not only provide ease of use and simplified browsing experience but it will also effectively reduce costs (financial, human resources, and spatial) typically incurred in managing multiple websites.

Women-only channels appear in agency websites, with a specific portion of the site devoted to the International Women’s Day activities. Around two have extensive women-only channels and only a few meet standards for use by persons with disabilities; only the Department of Social Welfare and Development (DSWD) and Department of Health have the comprehensive list of women-only services, while the DOST, and the Departments of Foreign Affairs and Trade and Industry meet the international guidelines for access by persons with disabilities. To enhance accessibility, workshops have been conducted an initial draft of a memorandum on universal design was finalized in 2016[32], although it is unclear whether this will be adopted by the current dispensation.

There are grievance and redress mechanisms in some agencies, for example, the DSWD provides feedback guidelines in the implementation of the government’s conditional cash transfer program, the Pantawid Pamilyang Pilipino Program[33]. But the question would be the response times of agencies in answering this feedback, although there is a 15-day requirement that agencies do so. The Bottom Up Budgeting project provide access to data on certain projects and programs implemented by different local government units across the country; according to Manasan (2016), citizens have access to primary data on the implementation of projects including project status, location, implementing agency and budget, however these are plagued by weak local government capacities.

As of writing, there are no electronic mechanisms for participation by citizens in rule-making, even if the Philippine Constitution provides for several means for Filipinos to participate in the legislation of laws, both at the national and at the local levels[34].

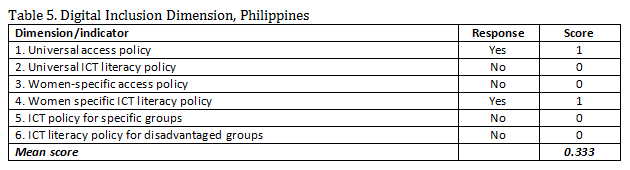

Dimension 3. Digital Inclusion

This dimension asks whether there are government policies and strategies designed to promote widespread benefit from communication and information technologies. This includes policies on universal access to technologies, the regulatory environment surrounding ICT development, and universal literacy of citizens. The scores for the Philippines are as follows:

Under the 2000 public telecommunications law, the NTC as the government regulator, is mandated to maintain competition in the industry to allow for reasonable telephone access to citizens. While there have been a few policies that the NTC has pursued to increase access to telecoms services, however, the growth in mobile and internet use has been driven by decreasing prices of smartphones. Access remains to be a significant problem in the country.

Recent initiatives by the government to widen access, such as initial forays into widening internet connectivity via the use of TV white space (i.e., spectrum unused by television broadcasting stations)[35] and the implementation of a free public wifi program have been laudable. However regulatory issues abound in the former, while the latter has been having difficulty getting off the ground due to issues in bidding and delays in public procurement; it is not clear whether the program will be undertaken by the DICT.

Access of remote communities (particularly in far-flung mountainous and small island communities) is still problematic, and the proportion of households using the internet outside of the capital centers is relative low, notwithstanding most of the town centers already having connectivity. A significant proportion of the country’s public schools does not have access to the internet, while vulnerable sectors, such as indigenous peoples, persons with disabilities, and the rural poor, are still are struggling with affordability and accessibility issues. More recently, the Foundation for Media Alternatives have released reports documenting the meeting among women’s and gender groups to discuss gender aspects of women’s access to ICTs[36].

For persons with disabilities, an existing policy on accessibility for web use by the persons with disabilities had been issued in 2010. The guidelines enjoins all the government instrumentalities concerned, to implement accessible website design using the technical guidelines recommended by the Web Design Accessibility Recommendation Checkpoints of the Philippine Web Accessibility Group (PWAG), a non-profit advocacy group of Filipino web designers organized by the council after its web accessibility workshop undertaken in the 2004 to 2007 period. The guidelines have been endorsed by the members of the PWAG, including the National Council on Disability Affairs, National Computer Center and the Department of Interior and Local Government[37].

There is no universal ICT literacy program/ plan, although the government department in charge of basic education requires secondary schools to offer “technology and livelihood education” in the vocational-technical track.

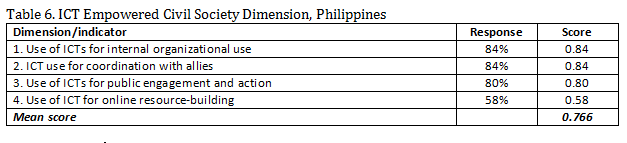

Dimension 4. ICT-Powered Civil Society

Thus, the study undertook a survey of 15 civil society organizations and political parties to measure extent of their use of ICTs in terms of:

- Internal communication;

- Internal and external messaging and communication;

- Coordination with other groups; and

- Online resource building.

Respondents were asked about the ICT readiness and use by civil society and other non-state organizations in the country. These were also asked to measure the extent to which independent organizes groups in the Philippines use ICT tools to achieve their objectives. The scores for the Philippines are as follows:

It had been difficult to measure this dimension because of the lack of survey information across a wide set of groups.; during the focus group discussions conducted under this study, civil society representatives provided some information on the sector’s use of ICTs. However, it was quite difficult to provide information to more specifically measure the use of ICTs by groups belonging to different categories. The survey results is provided in Appendix A. Note that the use of ICTs consist mainly of cellular phones and landlines, rather than the use of internet.

Given the fact that the groups in the survey are based in the national capital and in provinces around the national capital, the use of ICTs are at a very high level. However, their use of ICTs for fundraising and online resource building is relatively low. Nevertheless, because of the relative abundance of civil society groups and political parties, and the increasing penchant of Filipinos in terms of the use of social media applications to communicate with one another, the scores seem to be a reasonable representation of ICT use by civil society groups.

Dimension 5: Open Legal and Policy Ecosystem

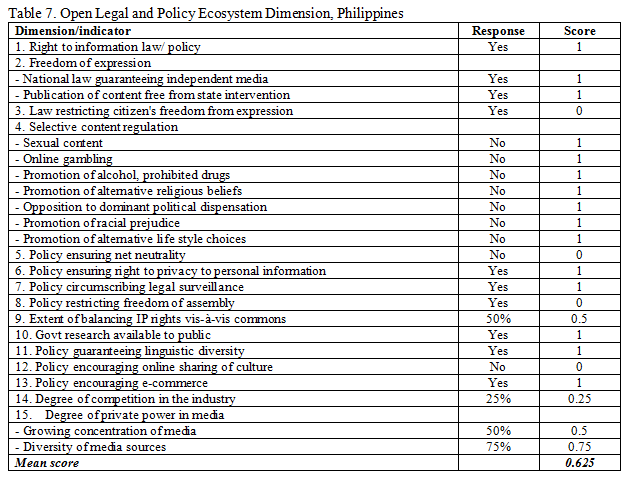

This dimension looks at the overall policy and institutional environment and whether it enables citizens to meaningfully participate in governance. This serves as an enabling backbone that influences the effectivity of ICT policies covered in the other dimensions. The scores for the Philippines are shown below in Table 7.

As stated above, the new Duterte administration has issued order that provides for all executive branch agencies to address ‘freedom of information’ requests from the public to promote transparency and strengthen public participation in governance. This is being implemented even if the formal mechanism to undertake this has not been created. For example, freedom from information has been requested from statistical agencies to provide public use datasets that would be utilized for academic studies.

The Philippine Constitution guarantees the general right of freedom of expression and freedom of the press and privately-owned media outlets are characterized as generally ‘vibrant and outspoken’ Media is a primary channel of citizens to information on matters of public interest, and “investigative journalism” has flourished in the country. The Philippine media has been one of the freest (and most free-wheeling) in the world as normally media is generally free from government constraints. Ironically, the country has been tagged as one of the most dangerous countries for journalists globally. This has nurtured a culture of impunity, which poses a direct threat to information freedom as it has a chilling effect on media. At the same time, other constraints include the establishment of a clearance system for media personnel to publish generally classified information and authorization to wiretap journalists on suspicion of “harboring terrorists.”

In terms of content regulation, generally there is no limitation on content with the following:

- Sexual nature: there is a provision in Republic Act 10175 has a provision on ‘cybersex’ and there are limits contained in several legislation acts, especially those that limit trafficking in women and children, including in online spaces. The restrictions can be found in the following laws: the Anti-Photo and Video Voyeurism Act of 2009 (RA 9995); the Anti-Child Pornography Act of 2009 (RA 9775); the Anti-Violence Against Women and Their Children Act of 2004 (RA 9262); and, the Special Protection of Children Against Child Abuse, Exploitation and Discrimination Act of 2003 (RA 7610).

- Online gambling: Republic Act 9487 allows the government owned casino company to promote online games; in fact, in the Philippines, online gambling and lotteries are very popular; the Philippine Amusement and Gaming Corporation, is the country’s monopoly on gambling, but it has issued a license to a private firm, which has recently been targeted by the President for a ban; there are provisions to prevent addiction and underage gambling;

- Alcoholic beverages and illegal drugs: RA 9165 on ‘dangerous drugs’ regulates manufacture and distribution of illegal drugs; but in general, for alcoholic beverages, there has been very few restrictions on online advertisements;

- Alternative religious beliefs: although a significant majority of the Philippine population is of the Roman Catholic faith, there have been very few online restrictions on different faiths; this can be traced to the preponderance of radio and television broadcasts containing Protestant and indigenous religions; these include broadcasting stations owned by the Iglesia ni Cristo (an indigenous Christian faith which was founded in the early 20thcentury) and by religious personalities such as televangelist Eliseo Soriano and Pastor Apollo Quiboloy;

- Opposition to dominant political beliefs: there are very few restrictions on online dissemination of different political beliefs, except for restrictions faced by the Communist Party of the Philippine; more recently, there is greater social media opposition opposing the current political dispensation; political advertisements are seen as part of the citizens’ exercise of ‘free speech’;

- Racial prejudice: there is very little or non-existent online views promoting racial prejudice, although sporadically, there are discriminatory posts against certain groups, i.e., Indian moneylenders, Filipino-Chinese entrepreneurs, but these are officially frowned upon and banned by the code of conduct of media practitioners in the country

- Alternative lifestyle choices: homosexuality is generally accepted, although more male homosexuality rather than female; more recently lesbian relationships are becoming more and more accepted.

In terms of net neutrality, there is current legislation seeking to assess whether the executive branch is addressing this concern. The Philippines has been epitomized as one of the countries in the world that have been utilizing Facebook’s Free Basics program.

There are laws that exist to guarantee right to personal information due to the Data Privacy Law, and parameters of legal surveillance are being defined. However, a recent paper published by the Foundation for Media Alternatives (2015) show that there are many state agencies that operate with intelligence-gathering functions, which appear to have overlapping and/or redundant mandates, and there is direct oversight mechanism in place—other than the regular courts—that could establish a clear boundary between lawful and unsanctioned surveillance, and ensure that state agents keep within such restraint.

Thus, the existing legal regime that is supposed to rein in potential abuse or misuse of surveillance is therefore very weak, beginning with the severely outdated anti-wiretapping law. This situation also results in serious regulatory gaps and at the same time, also deprives victims of unlawful surveillance operations of any reasonable access to justice. Consequently, there remains an urgent need to surface more information on this subject that could potentially lead to a transparent and responsible surveillance framework in the country

There is some balance between intellectual property (IP) rights and the creative commons only because the IP rights regime in the country is weak, although it is improving significantly. There also needs to be a corresponding effort to strengthen intellectual commons for the common good.

Generally, many government agencies have rules to allow public access to agency-funded research; but there needs to be further encouragement in this area. One example is the Department of Science and Technology requires publication of the studies that it normally funds.

Another example is the provision of maps for geographical information system needs of the public; the National Mapping and Resource Agency has provided low-resolution maps for a specific period.

While there are several government bodies that exist to promote linguistic diversity (Commission on Filipino Language, for example, has mandated the use of Filipino as a national language), there are very few mechanisms to encourage use of local languages; see for example, Bautista and Bolton (2008). This is because almost all literate Filipinos have basic knowledge of English, which is the language of choice that is used across government websites, and web administrators thus have very little incentive to devote additional resources to translate English-language posts to posts in the native language. At the same time, there are very few activities that encourage the online sharing of culture, although there are a few projects attempted by the government’s cultural promotion arm, the National Commission on Culture and the Arts, in the past to put a significant amount of its work online.

There is a national law that encourages e-commerce/ e-business activity, known as the E-Commerce Act or Republic Act 8792; however, the lack of competition in the telecommunications industry limits this growth. Other factors that have affected the growth of e-commerce are the lack of credit card holders and/or online payment systems, the requirement for a signature for credit card transactions, and security issues (one time pins are required for security purposes BUT serve as a disincentive to complete transaction) .Nevertheless, there has been a significant number of online marketplaces that have been developed, especially in the urban centers of the country. There are also attempts to develop marketplaces for agricultural products so that farmers can gain from the sales of their products.

While there is a diversity of viewpoints in information being provided by mass media, however, it has been observed that there is a growing consolidation in the industry and in fact mass media is dominated by very groups. Some of the recent attempts in consolidation include the purchase of a television station and several national news and business dailies by the owners of one of the two telecommunications companies in the country, the diversification into magazine business by a leading radio and television company and by a stakeholder of a telecommunications firm, and the acquisition of communication radio stations by a major radio network.

Nevertheless, there is still widespread variety of sources that Filipinos continue to enjoy. The growth of the internet and social media has also diversified the sources of news enjoyed by citizens in the country. There are also many online news sources such as the Rappler, a news website established by several television and print journalists, and the Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism, and many of the traditional print and television media outlets have also created their own web editions.

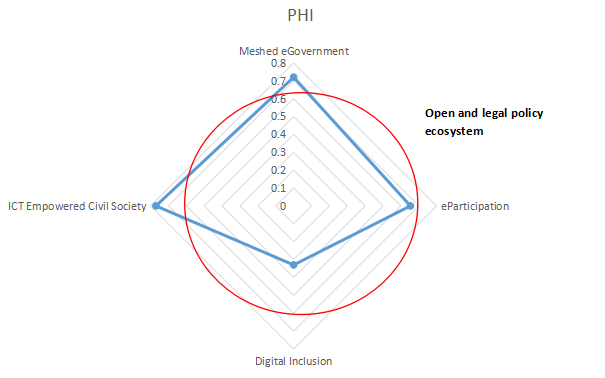

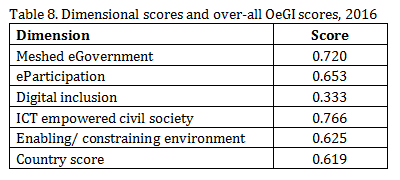

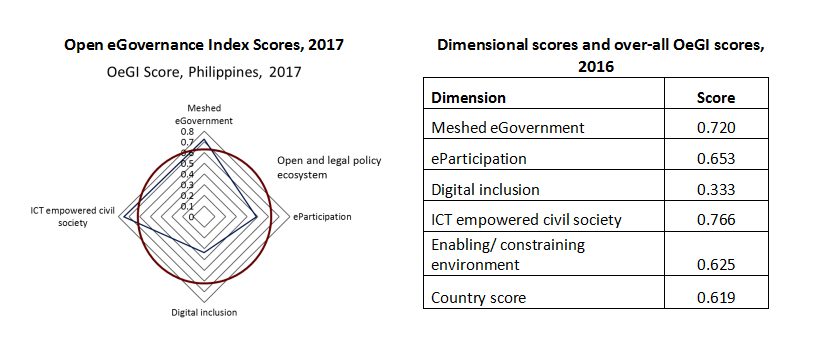

V. Summary of the Results and Implications

An illustrative summary of the scores for the Philippines are shown in Figure 2 below. The scores for the four dimensions are being shown in different quadrants in a diamond, while the score for the open and legal policy ecosystem is shown below as a circle. According to the illustration, the Philippines scores high in terms of meshed eGovernment and civil society use/ ICT empowered civil society dimensions but low in eParticipation and digital inclusion dimensions.

Figure 2. Open eGovernance Index Scores, 2017

Traditionally, the Philippines has ranked highly in terms of civil society use of ICTs. This is because the country has one of the most vibrant civil society sectors in Asia (and perhaps around the world), and coupled with the fact that Filipinos utilize social media significantly, shows the ability of non-government organizations and other groups to be able to use ICTs for internal communication and advocacy.

Also observed in this study is the significant score that the Philippines received in terms of the Meshed eGovernment dimension. Compared to the country OeGI score implemented in the 2011- 12period, there has been a general improvement in the policies and programs being implemented by the country in that dimension. Several policies such as an eGovernment framework and a government interoperability framework has already been adopted.

Nevertheless, the scores for the county in terms of eParticipation and digital inclusion leave a significant amount of effort to be desired. There are still several policies that need to be undertaken despite many initiatives that have been started in the past. Access policies, especially for disadvantaged sectors still need to be established, while standards and programs for ICT literacy need to be undertaken. There is also a continued lack of e-channels for participation in the bureaucracy, although efforts such as the freedom of information act had already been undertaken.

The open and legal policy environment, which is shown as a circle, provides the possibilities for growth and development in the various dimensions. This means that relative to the general environment, the country is still underachieving in terms of the supply of ICT services to the public and the ability to meet the demand for participation by the citizens in the country as evidenced by the relatively lower scores for digital inclusion and eParticipation dimensions.

As stated in the analysis above, part of the problem lies in the weak capacity of ICT agencies to be able to respond to the demands of open eGovernance. This implies a gap in political leadership, which in many ways illustrates the low capacity of the State, particularly key members of the ICT bureaucracy, especially in the past, in competently addressing the challenges of Internet governance.

At the same time, the lack of understanding and appreciation by the most senior public officials have hindered the development of reforms that can improve the utilization of ICTs in governance. Many programs and policies have been developed or removed with any clear rationale and there is a tendency among different agencies to implement ICT projects without consideration of impact on other ICT projects or policies.

This implies that State capacity was sorely lacking, resulting in many gaps in ICT governance that continues up to the present. It is after all government’s responsibility to lead in this, and political leadership was lacking time and time again—sometimes due to circumstances it could not control, but also due to circumstances it certainly could.

At the same time, structures for participation of civil society groups in governance, especially by ICT tools, has been sorely missing. Even if there has been a lot of demand for participation, the lack of government capacity to address this need constricts the ability of the public sector to address this issue. Even with the relatively high rankings of civil society groups, the demand for eGovernment and eGovernance services is relatively low, given the fact that the civil society groups utilize mobile telephony rather than the internet for communication. However, government has moved towards utilized internet and social media as means for relaying information and receiving feedback.

The low demand for services by civil society is due to the fact that capacities also of the sector is relatively weak given the poor environment to push capacity building, including literacy programs, for the marginalized groups. Clearly, access policy and literacy programs for the these groups and also for the general public needs to be prioritized. Civil society groups can also strengthen their own capacities by developing training programs on the use of ICTs, in which very little attention as yet has been provided.

This implies that the country should continue to enhance policies and programs that enhance access and use of ICTs, and at the same time, increase the mechanisms and processes that allow for greater transparency in governance and participation in decision-making. Policies for enhancing universal access, especially by women and basic sectors, need to be undertaken; at the same time, policies for implementation for ICT literacy programs need to be established beyond those being provided in secondary education. While mobile phones have become more widespread, its use for dissemination of public information and for sending citizen feedback still needs to be strengthened. Public participation can also be enhanced by developing policies that allow for greater use of government agency websites by marginalized groups.

VI. Conclusion

This study has attempted to assess the state of open eGovernance in the Philippines. In this study, the Philippines has scored relatively high in terms of civil society use and access to ICTs, while the indicators enhancing the so-called ‘back end’ of eGovernment services, Meshed eGovernance dimension, needs to be strengthened.

Clearly, the framework has managed to assess the state of eGovernance in the country by showing that, while there is a great demand for participation online, there is a great preponderance of policies and programs that the government needs to undertake. Policies that allow for greater inclusion and use by marginalized groups of ICTs, through the provision of infrastructure and education/ training, is necessary to improve the state of eGovernance in the country.

References

- Astrologo, Candido, Joseph Alberto Bulan and Sardis Catalan (2016). “Measuring ICT Development in the Philippines,” Presentation to the 13th National Convention on Statistics, Mandaluyong City, October.

- Bautista, Ma. Lourdes and Kingsley Bolton (2008). Philippine English: Linguistic and Literary Perspectives. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press.

- Foundation for Media Alternatives (2015). “Communications Surveillance in the Philippines,” typescript.

- Foundation for Media Alternatives (2016). “Facing the Future of Internet Governance in the Philippines: Between Honesty and Hope?” typescript, February.

- Manasan, Rosario (2016). “Assessment of the Bottom-Up Budgeting Process for FY 2016,” Philippines Institute for Development Studies Discussion Paper 2016- 23.

[1] Board member, project assistant and consultant, respectively, of the Foundation for Media Alternatives. This report has been written in consultation with the following board members, consultant and staff of the FMA: Alan Alegre, Emmanuel Lallana, Liza Garcia and Jessamine Pacis.

[2] Foundation for Media Alternatives proposal on the “Open eGovernance Index” project to the Making All Voices Count, November 2015.

[3] Ateneo School of Government (2012). “OPENNESS, ACCESS, AND GOVERNANCE IN ASIAN ‘NETWORK SOCIETIES’:Developing an Open Governance Index in Information, Communication and Knowledge, A Country Report for the Philippines,” Project Report, March.

[4] https://freedomhouse.org/country/philippines

[5] https://www.cpj.org/killed/asia/philippines/

[6] http://technology.inquirer.net/8013/more-filipinos-now-using-internet-for-news-information-study

[7] https://www.hrw.org/asia/philippines

[8] https://www.telegeography.com/products/commsupdate/articles/2016/09/02/philippines-competition-watchdog-rules-pldt-globe-deal-anti-competitive/

[9] http://i.gov.ph/e-government-master-plan-3/

[10] http://i.gov.ph/pegif/

[11] See HB 3612 in http://congress.gov.ph/legis/

[12] According to Wyn Yu, chair of the Internet Society, Philippine Chapter.

[13] http://www.dbm.gov.ph/wp-content/uploads/Issuances/2014/Joint%20Memorandum%20Circular%20/JMC%20no.2014-1_Jan22.pdf

[14] http://data.gov.ph/guidelines-on-open-data-implementation-jmc-no-2015-01/

[15] http://www.gov.ph/2016/07/23/executive-order-no-02-s-2016/

[16] https://www.foi.gov.ph/

[17] Open Government Partnership. Official Website. Retrieved 5 January 2017, from http://www.opengovpartnership.org/about

[18] Republic Act. No. 10173, Ch. 1, Sec. 2.

[19]http://www.dict.gov.ph/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/20120815-RA-10173-BSA.pdf; http://bap.org.ph/pdf/RA10173-IRR-data-privacy.pdf

[20] http://i.gov.ph/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/Draft-Data-Security-Policy-GCP-20160527.pdf

[21] : https://privacy.gov.ph/memorandum-circulars/

[22] http://www.dict.gov.ph/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/National-Cybersecurity-Plan-2022-1.pdf

[23] https://www.philgeps.gov.ph/

[24] http://janette.digitalfilipino.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/DOF-DTI-JDAO-No.2-Series-of-2006.pdf

[25] www.epaypilipinas.com/download/dti-dof-joint-department-administrative-order-no-10-01/; https://efps.bir.gov.ph

[26] http://sc.judiciary.gov.ph/jurisprudence/resolutions/2013/09/10-3-7-SC.pdf

[27] https://psa.gov.ph/civil-registration-services/online-applications-e-census

[28] http://egov4women.unescapsdd.org/report/institutional-stocktaking

[29] https://coconuts.co/manila/news/hotlines-911-and-8888-launched-today/

[30] http://i.gov.ph/policies/signed/memorandum-circular-rules-regulations-migrating-gwhs-dost-ict-office/annex-c-government-website-template-design-gwtd-guidelines/

[31] h http://i.gov.ph/ngp1/

[32] http://pwag.org/2015/07/list-of-philippine-sites-using-web-accessibility-features/

[33] http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/111391468325445074/Grievance-redress-system-of-the-conditional-cash-transfer-program-in-the-Philippines

[34] 1987 Philippine Constitution, Article VI, section 32.

[35] See http://icto.dost.gov.ph/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/Free-Wi-Fi-Project-TOR.pdf ; Marvin Sy. “Miriam seeks review of DOST public Wi-Fi project,” Philippine Star, September 26, 2015 http://www.philstar.com/headlines/2015/09/26/1504060/miriam-seeks-review-dost-public-wi-fi-project; also http://newsbytes.ph/2015/09/28/miriam-hits-underspending-at-ict-office-wants-wi-fi-project-completed

[36] Dempsey Reyes, “Digital gender gap-audit for PH launched,” Manila Times, April 7 http://www.manilatimes.net/digital-gender-gap-audit-ph-launched/321558/; see also http://www.rappler.com/move-ph/166497-digital-gender-report-card-filipino-womens-rights

[37] http://www.dict.gov.ph/paving-the-way-for-universal-design-and-web-accessibility-for-pwds/

[38] http://www.lawphil.net/statutes/repacts/ra2010/ra_9995_2010.html

[39] See Iris Gonzales, “PAGCOR clarifies ban on online gambling,” Philippine Star, December 24, 2016 http://www.philstar.com/headlines/2016/12/24/1656338/pagcor-clarifies-ban-online-gambling ; also https://www.rt.com/business/371264-duterte-gambling-philippines-ban/

[40] http://philippines.mom-rsf.org/en/findings/religious-media-outlets/

[41] See several rulings made by the Supreme Court on the freedom to broadcast political beliefs http://www.lawphil.net/judjuris/juri1969/apr1969/gr_l-27833_1969.html, http://www.lawphil.net/judjuris/juri1969/apr1969/gr_l-27833_1969.html.

[42] See the code of conduct of the Kapisanan ng mga Brodkaster ng Pilipinas or the national broadcasters’ association http://www.kbp.org.ph/wp-content/uploads/2008/04/KBP_Broadcast_Code_2011.pdf

[43] See Ruth Abby Gita, “Senator seeks to investigate practice of net neutrality in PH,” Sunstar Daily, June 23, 2015 http://www.sunstar.com.ph/manila/local-news/2015/06/23/senator-seeks-investigate-practice-net-neutrality-ph-414752

[44] http://www.mom-rsf.org/en/countries/philippines/[45] Alternative to Microsoft word, excel, powerpoint and other MS office.

0 Comments