The virtual face of trafficking: How technology facilitates gender-based violence in the Philippines

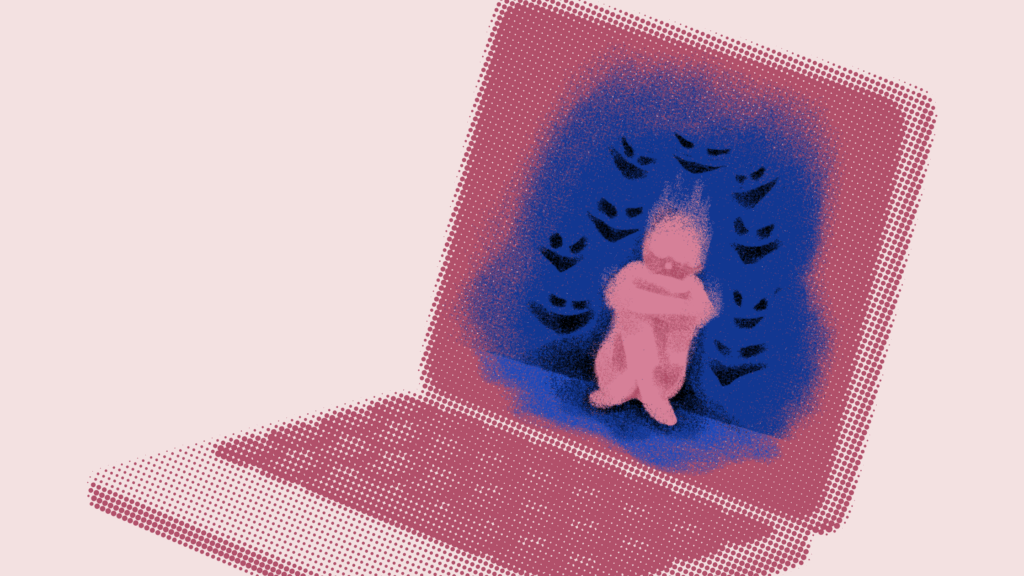

In recent years, trafficking in the Philippines has taken a disturbing turn as perpetrators use digital tools to recruit their victims. What was once happening mainly in remote brothels and through physical recruitment is now happening online, behind screens, under usernames, and in encrypted messages. This shift marks a dangerous rise in technology-facilitated gender-based violence (TFGBV), a form of abuse where digital tools are employed to carry out or amplify gender-based harassment. As internet access and smartphones become more accessible for Filipinos, more women and children also grow vulnerable to these forms of violence.

In the Foundation for Media Alternatives’s (FMA) 2025 Mid-Year Report on Online Gender-Based Violence, FMA documented the alarming escalation of digital harms, including trafficking-related abuses. The report highlights how women and girls are being targeted through social media platforms, job scams, and intimate partner grooming often leading to coercion, sexual exploitation, or forced labor.

One of the most alarming manifestations of TFGBV is the online sexual abuse and exploitation of children (OSAEC). For several years now, the country has been identified as a global hotspot for OSAEC, with children, sometimes as young as infants, being forced to perform sexual acts live on webcam for paying foreign perpetrators. These crimes are often committed by trusted individuals, even family members, using smartphones, video apps, and international payment platforms that shield perpetrators and make prosecution difficult. Likewise, cybersex trafficking of women is on the rise, with many being lured via social media job scams or deceptive online relationships. Once under control, victims are coerced into recording and/or streaming sexual acts, with traffickers threatening their victim, often through blackmail and surveillance, to maintain their silence and compliance.

Traffickers also exploit online job portals and messaging apps to recruit women for overseas jobs, only to subject them to forced labor or sexual exploitation upon arrival. With minimal regulation, the promise of work abroad becomes a trap. Another increasingly common method is through dating apps and social media grooming, where traffickers pose as romantic partners to manipulate victims emotionally before coercing them into sex work or trafficking networks. In more sinister cases, traffickers use sextortion, where they threaten to release intimate photos or videos of victims, pushing victims to a cycle of abuse.

New and deeply disturbing trends have also emerged:

- Online surrogacy trafficking, where economically vulnerable women are recruited through Facebook groups and digital platforms. They are tasked to carry pregnancies for foreign clients under coercive, exploitative, and unregulated arrangements. These women are often left without legal protections or postnatal support.

- POGO-linked trafficking, in which women are lured online for jobs in Philippine Offshore Gaming Operators (POGOs) and subjected to forced labor, prostitution, or 24/7 confinement in heavily guarded compounds. These operations often involve transnational crime syndicates.

- Infant-selling via Facebook, where babies are illegally sold through private groups disguised as adoption forums, often driven by poverty and desperation. These transactions are highly unregulated and pose grave risks to both mother and child.

- Organ trafficking, which has found a foothold in online communities. Women facing extreme financial hardship are coerced or manipulated into selling kidneys or other organs, with little to no legal or medical protection.

The consequences of human trafficking, be it online or physical, are profound and long-lasting. Survivors endure deep psychological trauma, knowing their abuse may have been recorded or shared permanently online. Many face stigma, threats, and lack of access to mental health care or legal support. Meanwhile, law enforcement agencies grapple with jurisdiction challenges, encrypted technologies, and the overwhelming scale of online crime.

While the Philippines has legal frameworks such as the Anti-Trafficking in Persons Act and the Cybercrime Prevention Act, the implementation is slow and authorities’ struggle with holding perpetrators to account due to the online nature of the crime. Given these lapses, combating TFGBV now demands coordinated action from the government, police, online platforms and civil society organizations. This means fostering close collaboration between police and digital platforms, enhancing digital literacy in local communities, providing trauma-informed legal and mental health services for survivors, and enforcing stricter oversight of online spaces where trafficking is known to occur.

0 Comments