Gender-based violence facilitated by new technologies entails human rights violation against women and girls on a daily basis. Since 2012, the Foundation for Media Alternatives (FMA) has been observing a growing number of online gender-based violence cases.

Online gender-based violence (OGBV) are “harmful acts directed towards an individual or a group of individuals based on their gender that are partially or fully carried out through or enabled by technology” (UN Women, 2019). It is a form of gender injustice and discrimination that takes place in online spaces (Global Citizen, 2021); and also an extension of the imbalance of power relations and a form of political, social and cultural control (SAFENet, 2022); and a spectrum of activities and behavior that involve technology as a central aspect of perpetuation of violence, abuse or harassment against women and girls (LEAF, 2021).

While OGBV is an isolated phenomenon that occurs online, it is also reflection of the patriarchal structure which permits men (in most cases) to feel as though they have the right to harass women and other gender online (Privacy International, 2019).

As of January 2022, the Philippines has 111.8 million total population. The country’s internet penetration rate stood at 68.0 per cent of the total population and the number of social media users was equivalent to 82.4 per cent of the population (WeAreSocial, 2022). However, social media users may not represent unique individuals due to multiple registrations in different social media platforms and used internet-enabled communication devices such as laptops, mobile phones and among others.

While these developments provide huge opportunities and benefits for the users, FMA continuously observed a continuum of violence, abuse and harassment in a form of proliferation of misogyny, sexist jokes, rape culture and even inciting direct and indirect threats in the form of comments, images, videos, or other multimedia formats, and these were facilitated through the use of information, communications and technology (ICT) and the Internet.

OGBV has increased significantly

From 2012 to December 2022, FMA has documented 659 cases of online gender-based violence in the Philippines. These are mostly sourced from media reports, received emails and messages from individuals, and personal sharing of survivors during public speaking engagements in different communities across the country.

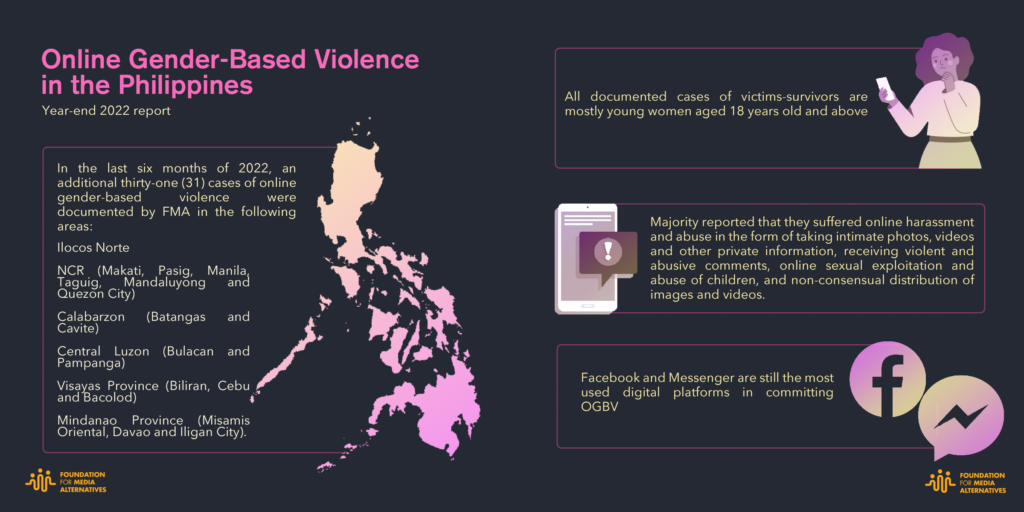

In the last six months of 2022, an additional thirty-one (31) cases of online gender-based violence were documented by FMA in the following areas: Ilocos Norte, National Capital Region (Makati, Pasig, Manila, Taguig, Mandaluyong and Quezon City), Calabarzon (Batangas and Cavite), Central Luzon (Bulacan and Pampanga), Visayas Province (Biliran, Cebu and Bacolod) and Mindanao Province (Misamis Oriental, Davao and Iligan City).

All documented cases of victims-survivors are mostly young women aged 18 years old and above, as well as minor girls. Some of them are working students. Majority reported that they suffered online harassment and abuse in the form of taking intimate photos, videos and other private information, receiving violent and abusive comments, online sexual exploitation and abuse of children, and non-consensual distribution of images and videos.

Facebook and Messenger are still the most used digital platforms while handy gadgets like smartphones and smart tablets are the technology devices most used in committing online gender-based violence. Some perpetrators also use encrypted messaging apps like Telegram and Viber to commit various forms of OGBV. This underlines how digital platforms play a central role in facilitating and providing new and exploitable mechanisms to abuse vulnerable groups like women and girls.

However, PNP-Anti-cybercrime Group has no definite numbers of handled cases related to online gender-based violence.

Unmasking the Offenders

This year, FMA found out that some state actors committed online gender-based violence. A former provincial governor was arrested in his city and was served a warrant of arrest and a warrant authorizing the search, seize, and examination of computer data on charges of violence against women and for violating the Cybercrime Prevention Act. The case stemmed from a complaint of his former partner for violation of Anti-violence Against Women and their Children Act of 2004 because allegedly the former governor threatened to spread the victim survivor’s private photos if she would not give in to his requests.

In Davao city, men in uniform were allegedly involved in the death of model and businesswoman . According to reports, the victim had “very sensitive information” against “suspected mastermind” which she was planning to use to blackmail him. Prior to the killing incident, there were allegations circulating on social media that the offender hurt the victim based on the victim’s Facebook post in April last year.

Meanwhile, a male video blogger in Benguet province was charged with sexual harassment under the Safe Spaces Act (Republic Act No. 11313), more popularly known as the “Bawal Bastos” law after he allegedly posted sexist comments against a woman to purportedly defend President Marcos.

Perpetrators of online gender-based are rarely held accountable in part due to the relatively low capacity to prosecute offenders (Broadband Commission, 2015). Societal barriers, limited legal recourse and other factors hamper the many women’s, particularly for girls and women living in poverty, access to justice. Such state of affairs exacerbate the already low reporting levels and the vicious cycle of abuse and violence.

Online gender-based violence is not separate from violence in the real world. It is a continuum and another manifestation of how the gender-based violence offline is reflected in the online world.

1These were documented with consent

![]()

0 Comments